Progressive Decentralization of Cryptographic Narratives

Original Title: “The Gradual Decentralization of Crypto Narratives”

Original Source: not boring, Old Yuppie

Startups are growing rapidly, not just in valuation but also in actual revenue. What is the main reason? Better ready-made infrastructure allows modern companies to write a few lines of code to accomplish what used to take years and millions of dollars.

For example, selling to enterprises. WorkOS helps you start selling to enterprise customers with just a few lines of code. WorkOS supports three features that enterprises require from any vendor: Single Sign-On (SAML), Directory Sync (SCIM), and Audit Logging (SIEM).

Development teams at rapidly growing B2B SaaS companies like Hopin ($5.65 billion), Webflow ($2.1 billion), and Vercel (over $1 billion) use WorkOS to become enterprise-ready in just a few hours, just like they use Stripe for payments or Twilio for communications.

Creation and narrative are part of what makes us human; stories allow us to coordinate across time and space. There is no denying that narrative is important.

However, as things become increasingly abstract and as we move more towards a world of abundance, what we do and buy is increasingly for things beyond mere survival—such as social capital, entertainment, and utility—making good narrative skills more valuable than ever. How to best achieve this has changed and become more complex.

Imagine, as a fast and extreme thought exercise, that you live in a hunter-gatherer tribe 12,000 years ago. Your tribe consists of about 100 people. Many are family members. Food is always the top priority. If you need to persuade the people in your tribe to go hunting, what kind of story do you need to tell, and how will you communicate this message?

Some very simple things, like “We need to go hunting now, or we will have no meat, and we will die,” said directly to your fellow tribespeople.

Everyone hears the message, and everyone understands the urgency, so they go out to hunt.

Things are clearly not that simple anymore. First, we don’t need to hunt for food. We open DoorDash or UberEats or Instacart or GoPuff or Farmstead, and food quickly arrives at our doorstep.

Imagine coordinating 100 people to decide what to have for dinner tonight.

A conversation I had at a wedding last weekend made me feel that spreading a message is quite difficult. Several friends were discussing why the Olympics' viewership was so poor. Of course, it feels strange without fans; the best athletes in America are underperforming, but the real challenge is that we don’t know the stories of other athletes. In the past, there would have been months of preparation, with introductions to American athletes on ESPN, The Today Show, and local newspapers. We would all watch the same programs, which would tell stories to persuade us to pay attention, carefully crafting a narrative.

On the other hand, in my little corner of the internet, NFTs have completely dominated the conversation.

NFTs have gained a voice in a growing niche market, not by telling a cohesive story—there is no NFT company—but by providing people with tools, ownership, and incentives to tell countless small stories about NFTs, thus forming a loud narrative.

Fred Wilson of Union Square Ventures wrote in a recent article titled “Opening”:

I’m not saying NFTs are the next big thing. I’m saying that consumer experiences built on the cryptocurrency stack are the next big thing, and NFT experiences are pointing the way.

In a world of abundance, attention is the scarcest resource, and it is hard to win people’s attention, requiring new strategies.

Technology, venture capital, markets, and cryptocurrency have also undergone the same shift, from top-down storytelling to bottom-up narrative building, where owning a narrative can be self-fulfilling and help companies:

Lower customer acquisition costs

Hire stronger employees

Build better partnerships

Attract follow-on investors at lower capital costs

Similar dynamics apply to venture capital firms, cryptocurrency projects, and even stocks. Stories turn into narratives, and narratives have real, measurable impacts.

So, how do you build a modern narrative?

Today, we will cover:

From storytelling to narrative building

Narrative techniques in venture capital and startups

Lessons from cryptocurrency

From Storytelling to Narrative Building

Every day, millions of companies and venture capital firms launch internal articles. They want to have a “conversation” around “X,” so they write articles about “X,” but… no one pays attention.

They are told that content is important, so they create content! Why doesn’t it work?

Corporate papers are a bit like sales, and according to Alex Danco, we have moved past the sales phase into a better stage: world-building.

(Note: This is separate from the concept of “world builders,” although successful “world builders” certainly use stories to create a huge effect).

In “world-building,” Danco believes that everything is about sales, but sales alone are not enough. You need to build a world. In a “rich narrative and complex choice world… you need to create a world so rich and engaging that others are willing to spend time in it, even if you are not there propagating it.”

This means telling multiple related stories and repeatedly telling them in a way that makes your overall story clear enough for others to repeat it themselves.

In a follow-up conversation with Jim O'Shaughnessy about “Infinite Loops,” Danco provided more insight into why world-building is important today.

In a world of abundance, when you can read, watch, or listen to anything for $0, what is restricted? Attention.

Or, as Danco puts it, “What is starting to become scarce is people’s actual interest in you.”

In an age of abundance, even in an age of rich stories, the ability to tell a great story is a key cornerstone. But having just a story is not enough. You need to get your community involved in the narrative.

Do stories and narratives sound like the same thing?

According to Merriam-Webster, stories and narratives are synonyms, but we will distinguish between the two.

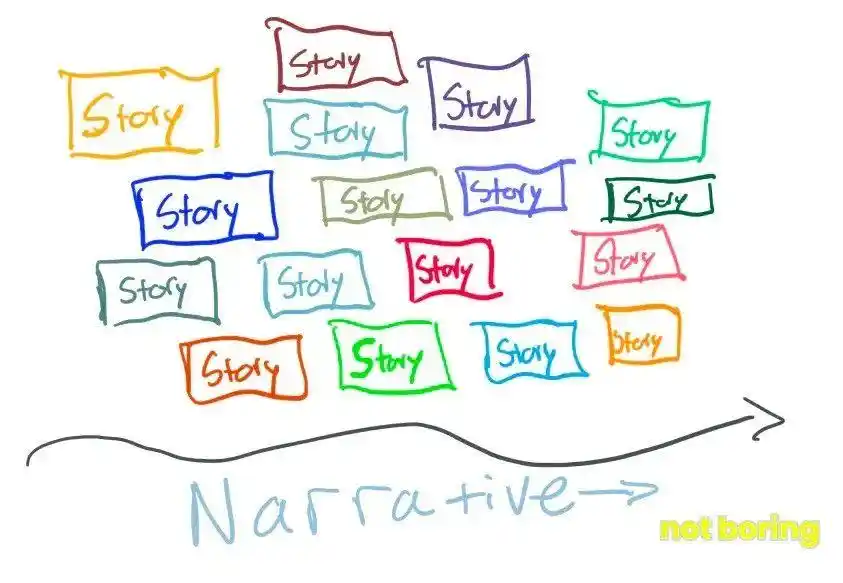

A story is discontinuous. An article, an event, a customer experience. Someone might say, “Have you heard the story about Company X doing Y?”

A narrative is made up of all the stories about a company, which concretize into people’s overall perception and discourse about the company. The narrative around a company is akin to its reputation or brand.

If a company writes a blog post about its origins, that’s a story. If an investor talks about the company on a podcast, that’s a story. If a founder tweets a topic, that’s a story. If a customer tells their friend about their good interaction with customer service, that’s a story. If a developer tells other developers that the company’s API is clean, that’s a story. If TechCrunch reports on their latest funding round, that’s a story.

These individual stories add up to form a narrative that is constantly changing and evolving but has a direction, scale, and tone.

However, a narrative is also composite; positive stories add up, stories reinforce the narrative, and the narrative reinforces the stories. There is no formula for forming a narrative, but the components are:

The number of stories told

The ratio of positive to negative stories

The coherence of positive or negative attributes

The number of different storytellers

The credibility of the storytellers to the target audience

Confirmatory updates

The persistence of stories over time

For the narrative of a company or project, the best approach is to have many credible people to the target audience repeatedly tell stories with roughly similar positive themes over a long period, incorporating new examples of the same positive themes. The more authentic and less coordinated it all feels, the better.

This is hard to achieve, especially since it requires organic, perfectly timed seeding by the company or team and its core supporters. However, when it works, it is a powerful thing, and its benefits compound over time.

The longer people believe in a company, the more likely they are to believe things about that company.

A Current Good Example is the Relationship Between Apple and Facebook

The narrative surrounding Apple is that it is a world-class design and privacy-first company, and its products are good for those who own them. This narrative has been in place since the time of Steve Jobs and continues to this day. It is armor. Anything that does not align with this narrative gets deflected; anything that meets this narrative gets amplified.

The claim that the 30% revenue from the App Store is anti-competitive has had little impact on the company. Apple’s recent decision to set backdoors in iCloud and iMessage sparked outrage among privacy advocates but did not damage the company’s good reputation.

Facebook’s narrative has been shaped by founder Mark Zuckerberg’s writings, the film “The Social Network,” the company’s old motto of “Move fast and break things,” his stammering speeches, and the Cambridge Analytica scandal. The positive impact of Facebook on small businesses and the free WhatsApp messaging service connecting over a billion of the world’s poorest internet users is rarely discussed.

If you look at the activities of these two companies over the past few years with fresh eyes, you might think Facebook is the good company and Apple is the evil company, but we see everything through pre-existing narratives. These take time to shift.

Once a narrative is set, it takes time to shift. One reason for the respective narratives could be that Apple (a primarily hardware company) has a 29x PE multiple, while Facebook (a software company) has a 26x multiple.

These are extreme examples involving two of the world’s most valuable companies, but similar phenomena have been playing out on a smaller scale. Stripe is a great modern example of a company that has built a strong narrative around itself, achieving the sacred double: 1) People love to talk about Stripe, 2) When they do, they give it the benefit of the doubt.

Apple, Facebook, and even Stripe built their narratives when competition was less fierce. But their successful tricks may not work for you.

The old way to build a positive narrative is to tell a consistent story about yourself over time. The new way is to have others tell your story for you, either directly or through association.

Narrative in Venture Capital and Startups

The idea that companies and funds need to tell their stories is not new; it’s what marketing and PR departments have always done.

In 2009, Tom Foremski wrote an article on ZDNet titled “Every Company is Becoming a Media Company…” about Cisco. That same year, Andreessen Horowitz launched the first venture fund to leverage the power of storytelling.

When a16z launched and Foremski wrote that article, the big idea was that companies and investors should be able to tell their own stories directly.

Today, the power lies in sharing the microphone.

In June, a16z launched its own media brand, “Future,” implementing a dual approach to its owned media strategy, which is clearly effective. Some articles on Future are written by a16z partners, but many are written by entrepreneurs within or around the a16z ecosystem. When the site launched, quite a few journalists expressed dissatisfaction with a16z’s attempt to bypass the media and directly disseminate their messages, but that was not its intent. I suspect their posts won’t get as many views as articles on TechCrunch. What it really aims to do is create a place where like-minded entrepreneurs and investors can come together to paint compelling stories about the future.

Similarly, individual capitalist Josh Buckley launched Hyper in July. According to its website, Hyper is a VC accelerator that “looks at companies through the lens of our unique distribution and community features.”

Everything about Hyper is oriented around this new distribution model, as are AngelList, Sequoia, Harry Stebbings’ 20:VC, and of course a16z. The people involved have large audiences; Naval has a massive following on Twitter. Harry Stebbings has a podcast that is very popular among audiences. Sriram Krishnan runs a top Clubhouse show.

Individually, any of these brands or figures could tell a compelling story. Over time, they can collectively shape a narrative.

This is also why many startups welcome more individual investors, especially those who can help tell their stories, into the capital markets. This creates more surface area for more people to tell the company’s story, allowing the company to control its narrative.

Looking back, the formation of a story also includes the number of stories told, the number of storytellers and their credibility, the consistency of the positive aspects of the stories, and the persistence of the stories over time. A collaborative venture capital fund composed of a group of credible individuals has the right credibility and incentives to build a company’s story over time.

That’s why a16z is building a collaborative media brand, and why Hyper has the potential to be a valuable investor in its portfolio companies. This is also what I’m trying to achieve in “Not Boring”: to find companies with compelling products and stories and help them accelerate turning those stories into cohesive narratives that cut through the noise.

Everyone tweeting the same thing is better than no one doing so, and it may help with early momentum, but it’s more important to figure out how, over time, everyone at the capital table can truly lend credibility to the company’s narrative.

Better yet, these investors should be part of a diverse group of stakeholders who have the motivation and ability not just to parrot but to amplify the story, contributing to the emerging real narrative.

The Best Guide on How to Do This Comes from Cryptocurrency

Lessons from Cryptocurrency

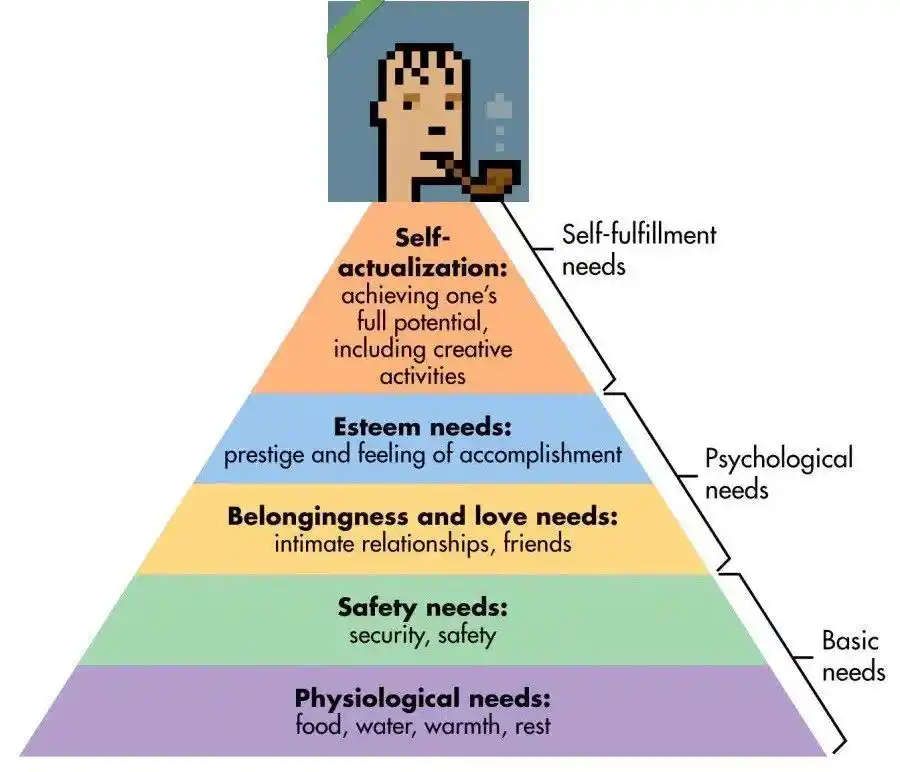

In a world of abundance, we spend more money and time on the higher levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Most of the things we buy today are not needed, and we don’t need to spend time on them. Even the best, most useful B2B SaaS, no matter how important it seems, is a luxury. The beauty of NFTs, and why they are such an interesting case study, is that they are the purest and most honest distillation of this trend.

What people mock—“These are just stupid JPEGs!”—is also what makes them so rich narratively. They are largely empty vessels into which communities of owners and supporters can pour stories, turning them into a narrative. Studying what makes certain NFTs valuable is enlightening for those trying to build a narrative today.

Let’s start with CryptoPunks, which are considered valuable because they are OG NFTs, but there are other old NFT projects that haven’t taken off like Punks. My guess is that the reason Punks are valuable is that the stories surrounding them have accumulated and compounded into a positive narrative.

When a Punk sells for over $7 million, that’s a positive story.

When Jay Z buys a Punk, similarly.

When Punk comics turn certain Punks into characters in a story, that’s both a literal story and a story about the potential value of this IP.

The fact that CryptoPunks are old is not the reason they are valuable; it’s just a story that satisfies an overarching narrative: “These are the most legitimate NFTs.”

Looking at a newer project can also be useful to see how these narratives begin to form.

NFTs start here, and the narrative of millions of small stories will be written by the community, with stories along the way.

I think this is why certain NFT projects, even new ones, do well while others fail. Pudgy Penguins, Art Blocks, and Bored Ape Yacht Club have captured people’s attention and imagination, which in turn tells the story of the project, forming a narrative around it that gives it lasting power. They have built a world that others are willing to spend time in and provided them with clear story components.

Telling a shared narrative makes it more fun and immersive for everyone involved—NFTs are a blend of investment, social networking, community, and entertainment—and makes NFTs more valuable. That’s why I believe that a plethora of NFTs won’t harm value by diluting scarcity; rather, it could make certain NFTs more valuable. If a key factor of a narrative is the number of stories told by credible people, then getting more people to co-own an asset and tell stories about it should accelerate the emergence of the narrative.

I wanted to experiment with this argument. I found PartyBid for Punk #8721, Hooka Punk, put in 1 ETH, and invited people to join the party.

Join the Hooka Punk PartyBid

All of this is happening in a small narrative petri dish from the bottom up. As Fred Wilson pointed out, what’s happening in NFTs is showing the way. Narratives transcend cryptocurrency, extending to anyone trying to form narratives around their companies, products, or projects, including:

Clearly stating your purpose so others can use it in their own stories.

Getting people genuinely involved in what you’re doing and motivating them to tell their own stories.

Partnering with credible allies to tell your story in new ways to the right people.

Embracing authenticity rather than trying to over-glamorize (unless you’re Apple).

Providing a coordinated space for stakeholders, like a Discord server.

Amplifying their stories when they are incorporated into the main narrative.

Staying open to the million ways narratives can evolve.

This is essentially the gradual decentralization of narrative. Create components, tell the initial story, and then step aside. This may feel uncomfortable, and it’s not a method that suits everyone, but in the competition for attention, those who are willing to relinquish control and let the narrative have a life of its own within the community will win.

Of course, what we see now is just the beginning. As DAOs and teams take a larger share in investment and company building, a significant source of their power will be allowing more people to tell stories, shaping the narratives around projects and companies. A decade from now, attempts to tightly control narratives will seem outdated.

A decade ago, every company was a media company, and companies and funds invited more voices to co-create their narratives; the next decade will be about community-driven narratives and dissemination.

“Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?”