Quantitative Analysis: How Decentralized and Censorship-Resistant is Ethereum After the Merge?

Original Title: 《Consensus at the Threshold》

Author: Takens Theorem

Compiled by: aididiaojp.eth, Foresight News

Consensus is the foundation of cryptocurrency, but it also raises questions. The merged Ethereum is no exception: there are concerns about the centralization of proof-of-stake (PoS) validators and the loss of censorship resistance.

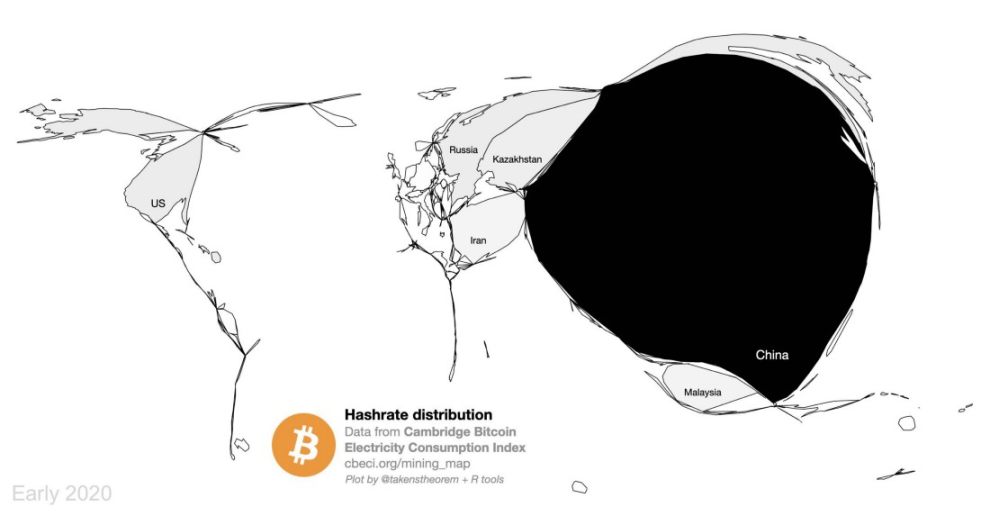

This is not a new debate. Before the merge, there were already worries about the concentration of validators and changes in the censorship regime after Ethereum's merge. Of course, this issue is not unique to Ethereum; for example, 60% of Bitcoin's hash power was once concentrated in China, but the distribution of Bitcoin mining underwent a fundamental change in less than two years, with the U.S. now dominating (over 35% at the time of writing).

Approximate hash rate changes in the Bitcoin network from 2020 to 2021

There are reasonable concerns in these debates. The goal of cryptocurrency is to create a neutral, censorship-resistant, and decentralized system, with enough participants to withstand attacks. But even in seemingly optimistic scenarios, the network still faces theoretical risks, as unknown attack vectors mean that any centralization increases the likelihood of such attacks occurring.

Next, we will conduct a simple quantitative analysis of the concentration of miners and validators before and after the merge.

Before and After the Merge

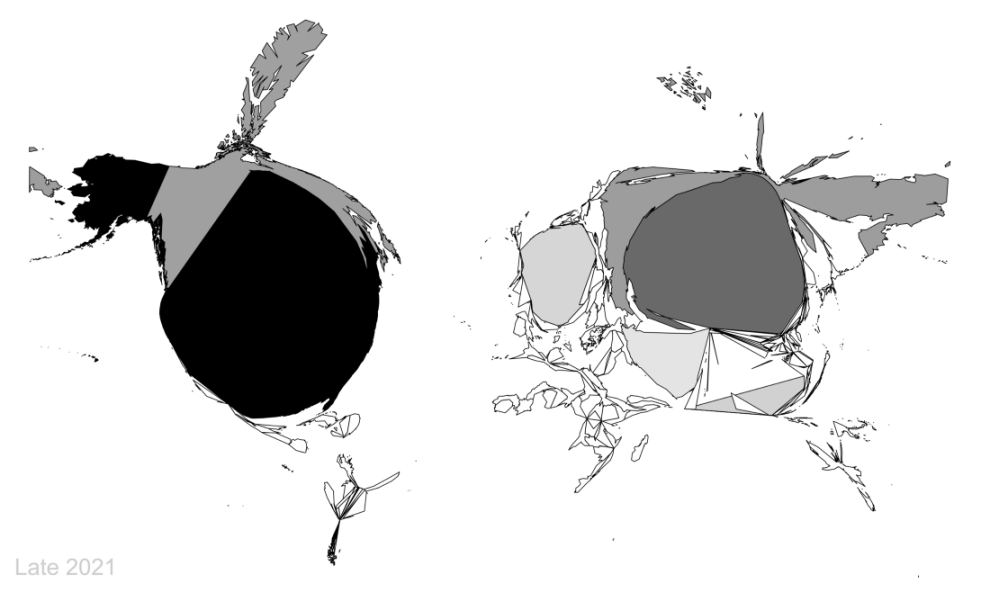

Taking thousands of blocks before and after the merge as an example, we can examine the concentration of block proposer addresses (miners and validators) associated with each block. Before the merge, only a dozen mining addresses were associated with rewards, including Ethermine and others. After the merge, thousands of addresses were associated with validators. After crossing a sharply changing threshold, the difference in the number of addresses that uniquely reward validators became significant.

Data source: Etherscan

This is a promising feature of PoS. While participation as a validator requires a stake of 32 ETH, there are still at least thousands of participating entities that meet this requirement.

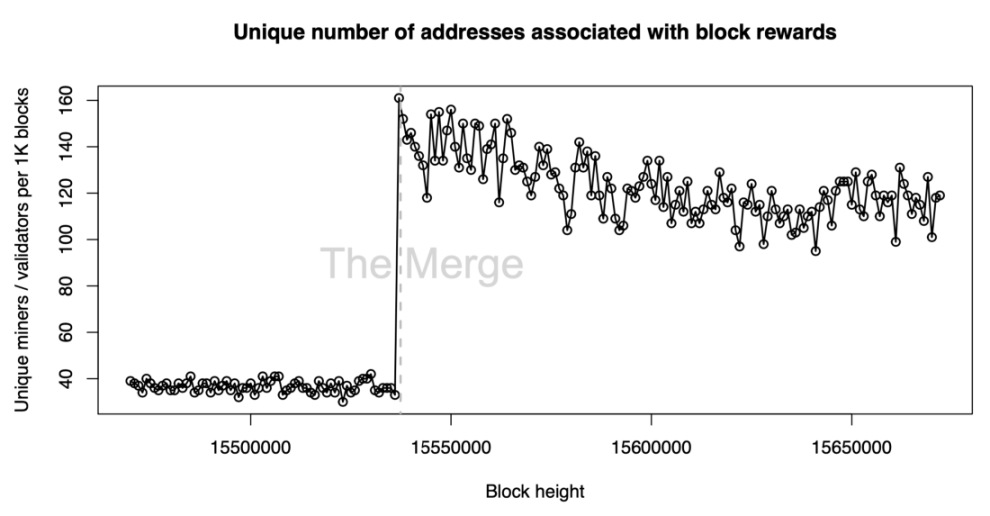

After the merge, the concentration of reward recipients remains high. We attempt to reflect the concentration of rewards per 1000 blocks through Gini coefficient analysis (a measure of income distribution among individuals). The Gini coefficient ranges from 0 (completely shared blocks) to 1 (belonging to a single validator). We can also calculate the percentage of the top 3 blocks associated with addresses. The two lines in the chart below show how this analysis changes over time:

Data source: Etherscan

The Gini coefficient is not a perfect measure, but it has some reference value. While the number of validators is increasing, they are also becoming more concentrated in a proportional manner. The control percentage of the top 3 seems similar, but there is a statistically significant difference between the left and right sides of the chart, with the concentration increasing by about 2% (p < 0.005) after the merge. Despite the trend toward decentralization, significant concentration is shown under both metrics.

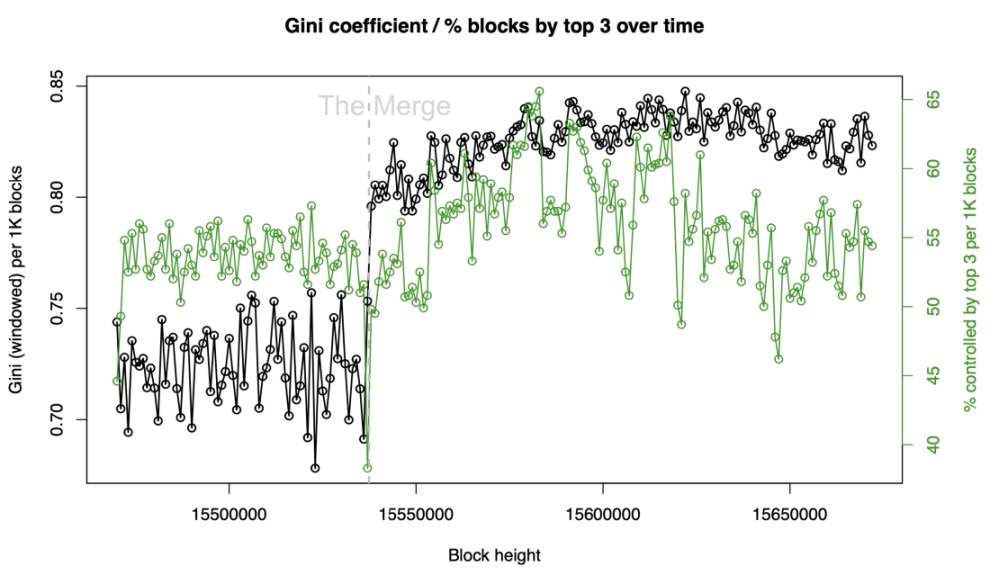

This centralization may be inevitable, as the top 5 validator pools hold nearly 80% of the staked Ethereum. Additionally, PoS has a high degree of liquidity. Validators can build their blocks anywhere and can switch immediately to services built from other blocks. This marks a shift in PoS: further decoupling between block proposers and builders.

How can we ensure that the centralization of block building services does not overly impact the operation of the network? Jon Charbonneau provides a detailed analysis of this decoupling and how to optimize it within the protocol in a Delphi analysis report. As Vitalik Buterin summarized in a recent article, one approach is to balance optimizing constraints on block builders and reducing the burden on block proposers.

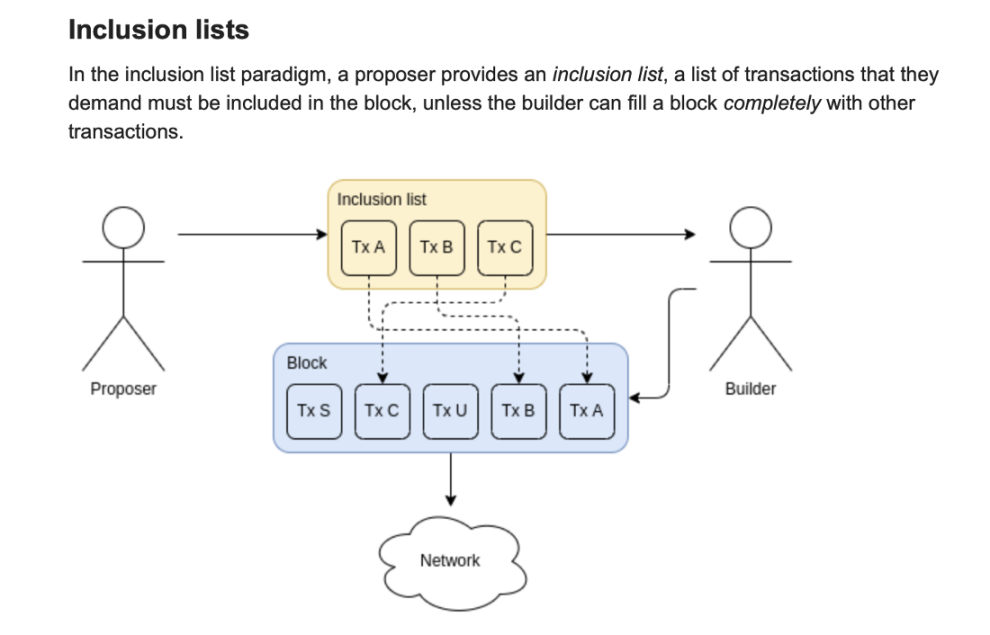

Vitalik considered several designs to achieve this balance, such as "inclusion lists"

Censorship Resistance

Some developments after the merge have heightened concerns about concentration. For example, influenced by U.S. sanctions, some block builders avoid transacting on Tornado, resulting in a 30% to 40% reduction in these privacy-protecting transactions. The controversy here is whether users need to avoid using addresses or protocols sanctioned by OFAC. Although the U.S. government has not made specific recommendations, compliance with local jurisdiction is reasonable, but the ambiguity of this situation has sparked some debate.

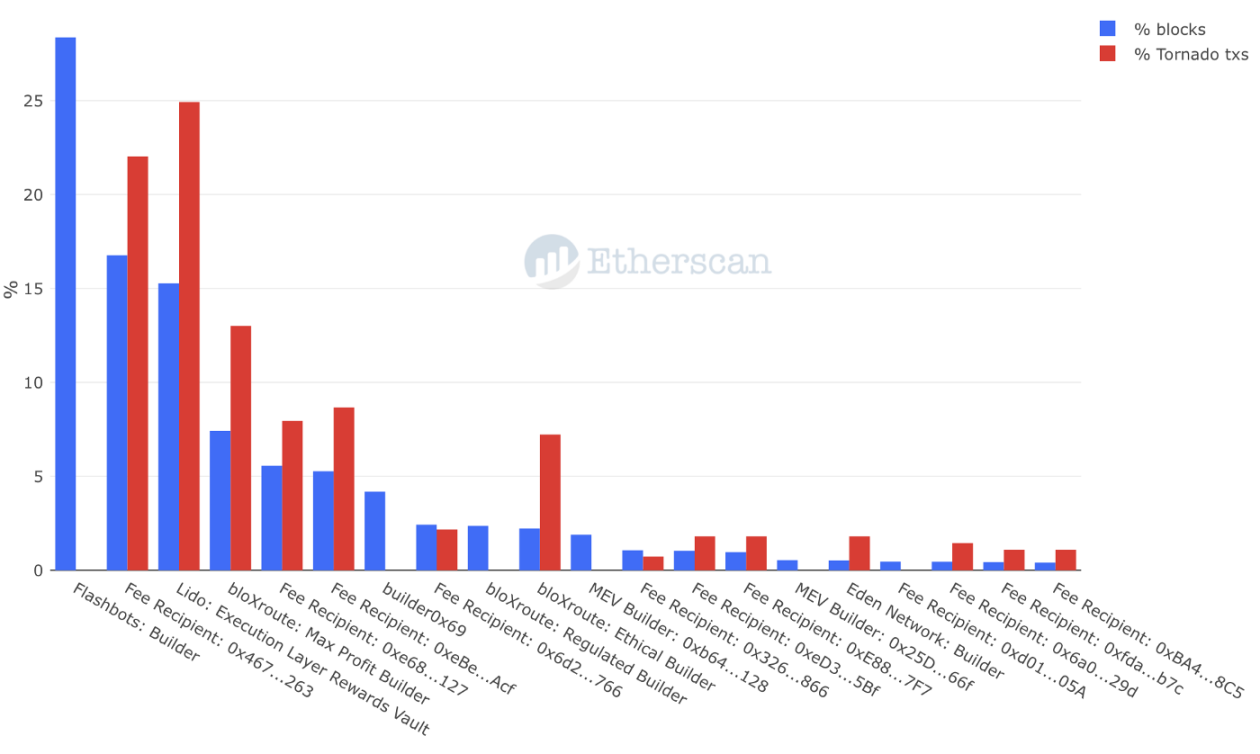

Etherscan data shows a recent breakdown of validators by the percentage of blocks generated and the percentage of transactions proposed through the Tornado router (0xd90e2f9). You can see Flashbots, the largest block generator, on the far left, verifying 0% of Tornado transactions. Others may also use Flashbot's relayers.

Data source: Etherscan

Charbonneau emphasizes the importance of this issue and states bluntly: "Ethereum can survive on higher fees, but it cannot survive on censorship." One existing tool the network has to address this issue is slashing. Validators may penalize others for such practices. Slashing occurs occasionally on the network and is partly addressed by solutions provided by Eric Wall and others.

Note: Slashing is intended to prevent malicious validator behavior and incentivize network participation in the blockchain.

Conclusion: Decentralization

As mentioned above, PoS introduces significant liquidity in consensus, which was not present in GPU and proof-of-work before the merge. But liquidity is a double-edged sword: if you can quickly shift toward decentralization, you can also quickly shift in the opposite direction.

These highly "mobile" validator networks exhibit two types of decentralization: potential and realized. All networks have this attribute, but PoS may have a higher rate of change on this gradient, meaning it can rapidly shift between extremes. In other words, validators can easily move their operations physically and across block building services. While the physical validators and corresponding nodes may remain unchanged, the network's wiring can theoretically centralize very quickly: from independent block building to reliance on centralized builders.

Ethereum now has hundreds of thousands of unique validator addresses. This means there are many overlapping entities (the "witches' problem"; for some statistics on users, see Etherscan), but it still indicates that Ethereum's PoS has extremely high potential for decentralization. If all depositors run their own nodes, there could be thousands of independent entities proposing blocks.

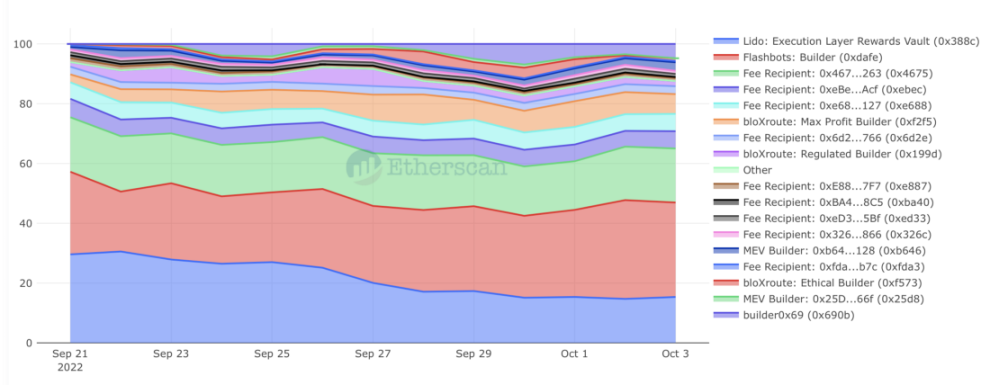

However, the decoupling of proposers and builders brings a second source of centralization: block builders. Builders can influence the profit margins of node operators, and there are incentives between builders and proposers, meaning a very successful builder can reduce the network's decentralization, for example, validators may flock to well-designed building tools. As shown in the chart from the past two weeks, Flashbots (red band) has begun to dominate block building, accounting for over 30% just from its main fee addresses. This somewhat diminishes Ethereum's realized decentralization.

Data and plotting using Etherscan tools

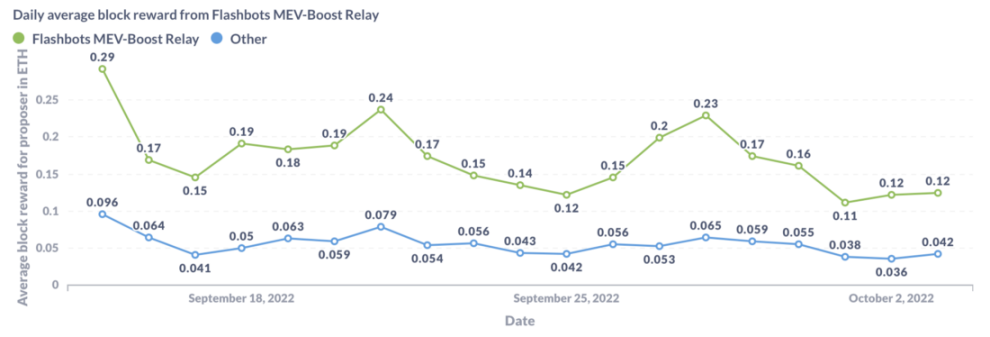

Flashbots shares a transparent dashboard reporting all relaying and building activities. (They recently announced goals for shared infrastructure, creating grants around transparency, and ultimately contributing to more decentralized block building.) At the time of writing, their total dominance is about 40%, and it becomes clearer why they are an attractive resource for validators:

Data source: Flashbots Transparency Dashboard

We look forward to the ideas shared by Charbonneau, Buterin, and many other developers to be further realized, not only in optimizing energy efficiency and flexibility in protocol adjustments but also in achieving Ethereum's massive potential for decentralization after the merge.