Decrypting the Silvergate and Silicon Valley Bank Crisis: A Gamble in the Dollar Interest Rate Hike Cycle

Written by: 0xmin, Deep Tide TechFlow

U.S. regional banks are collapsing one after another!

On March 8, Silvergate Bank, known for its cryptocurrency-friendly policies, announced its liquidation and will return all deposits to customers.

On March 10, Silicon Valley Bank, which provides financial services specifically for Silicon Valley tech companies, sold $21 billion in marketable securities, suffering an $1.8 billion loss, and is suspected to have liquidity issues. On Thursday, its stock price plummeted over 60%, with a market value evaporating by $9.4 billion in a single day.

This has also frightened many Silicon Valley bigwigs.

Peter Thiel's venture capital fund, Founders Fund, directly advised the companies it invested in to withdraw their funds from Silicon Valley Bank. Y Combinator CEO Garry Tan also issued a warning, suggesting that invested companies consider limiting their exposure to lenders, preferably not exceeding $250,000…

Even more frightening is that Silicon Valley Bank may be the first domino to fall, affecting not only other U.S. banks but also potentially striking a blow to tech startups in Silicon Valley.

What exactly happened?

Today, we will tell a story about how banks go bankrupt.

Understanding the Banking Business Model

First, we need to understand the business model of the banking industry.

In simple terms, a commercial bank is a company that operates with money; the bank's business model is fundamentally no different from other businesses—buy low and sell high, except the product is money.

Banks obtain money from depositors or the capital market and then lend it to borrowers, profiting from the interest rate spread.

For example: a bank borrows money from deposits at an annual interest rate of 2% and then lends it to borrowers at an annual interest rate of 6%, earning a 4% interest spread, which is net interest income. Additionally, banks can earn profits from basic fee-based services and other services, which is non-interest income. Net interest income and non-interest income together constitute the bank's net income.

Therefore, if a bank wants to earn more profit, similar to selling goods, the best scenario is to have no inventory, meaning to lend out all the low-cost deposits at high prices, as deposits come with costs and interest must be paid to depositors.

This also constitutes the two sides of a bank's balance sheet.

Owner's Equity + Liabilities: Owner's equity is the capital, and the deposits customers place in the bank are essentially borrowed by the bank from customers, which are liabilities. For banks, the more liabilities, or deposits, the better, and the lower the cost, the better. Banks like Silvergate, which focus on being cryptocurrency-friendly, primarily attract deposits from large companies in the crypto world by providing unique services like the SEN network.

Assets: Corresponding to deposits, the loans issued to customers are the bank's receivables, which are assets, including various types of mortgages, consumer credit loans, and various bonds, such as government bonds, municipal bonds, mortgage-backed securities (MBS), or high-rated corporate bonds.

So, how does a bank with such a simple business model go bankrupt?

When a bank encounters a crisis, it means there is a problem with its balance sheet, usually in two situations: bad debts; maturity mismatch.

Bank Bad Debts: Under normal circumstances, banks need to recover loans to generate profits. If the loans issued or bonds purchased are worthless and default, the bank will face actual losses. Lehman Brothers, which went bankrupt during the subprime mortgage crisis, did so because it held a large amount of bad loans, and the asset losses on its balance sheet far exceeded the bank's equity, meaning it was insolvent.

Maturity Mismatch: The maturity of the asset side does not match the maturity of the liability side, mainly manifested as "short deposits and long loans," meaning the funding sources are short-term while the use of funds is long-term.

For example, if you need to pay rent on the 1st of this month, but your only cash flow income is your salary paid on the 10th, your cash inflow and outflow do not match, leading to a maturity mismatch, which is a liquidity crisis. What to do in this situation? Either sell your assets, such as stocks, funds, cryptocurrencies, etc., to convert them into cash, or borrow some money from friends to tide over the current crisis.

Returning to Silvergate and Silicon Valley Bank, the maturity mismatch is the reason they fell into crisis.

Not only these two banks, but various crypto unicorns that previously fell into crisis, Celsius, Bitstamp, AEX, etc., all went bankrupt due to liquidity crises caused by maturity mismatches.

Ultimately, this is all related to the Federal Reserve's interest rate hikes; they are all corpses under the dollar cycle.

How Did Silvergate Go Bankrupt?

Founded in 1986, Silvergate Capital Corp (stock code: SI) is a community retail bank located in California, which remained quiet for decades until Alan Lane decided to enter the crypto industry in 2013.

Silvergate Bank's main label is that it is a very cryptocurrency-friendly bank, not only accepting deposits from crypto trading platforms and traders but also establishing its own crypto settlement payment network, SEN (Silvergate Exchange Network), for cryptocurrency settlements, helping exchanges and customers better manage deposits and withdrawals, becoming an important bridge between fiat and cryptocurrencies, such as FTX has always used SEN for fiat deposits and withdrawals.

As of December 2022, Silvergate had a total of 1,620 customers, including 104 exchanges.

When the crypto bull market arrived, a large amount of capital flowed in, and customer deposits from the crypto industry surged, especially because the existence of SEN forced a large amount of funds from exchanges to be deposited in Silvergate.

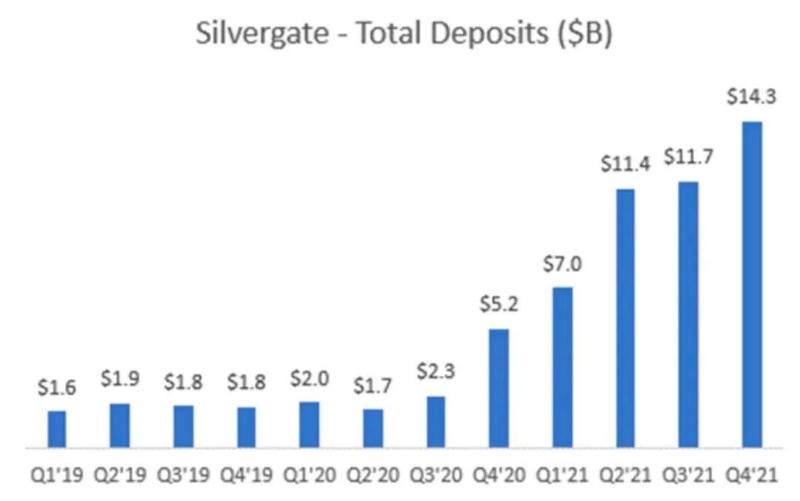

From Q3 2020 to Q4 2021, Silvergate's deposits skyrocketed from $2.3 billion to $14.3 billion, an increase of nearly 7 times.

Being cryptocurrency-friendly and the crypto bull market led to a rapid expansion of Silvergate's liabilities, i.e., deposits, but this forced the company to "buy assets." The loan issuance cycle was too long, and this was not Silvergate's strength, so it chose to purchase billions of dollars in long-term municipal bonds and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) during 2021.

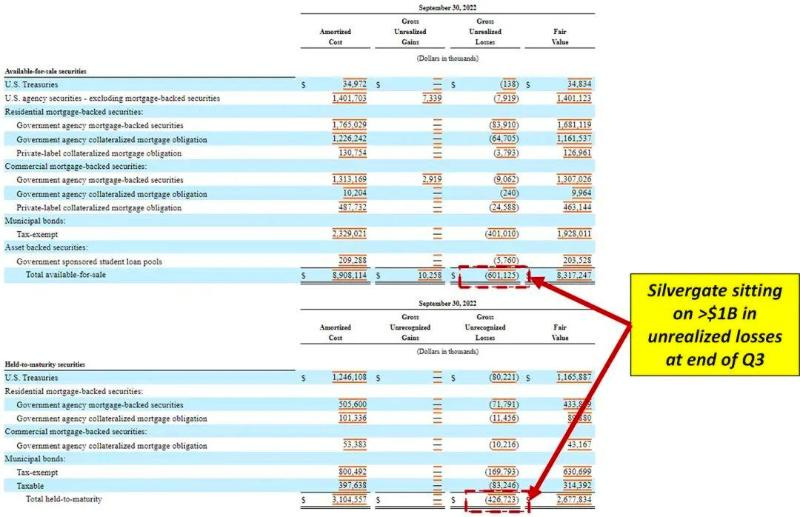

As of September 30, 2022, the company's balance sheet showed about $11.4 billion in bonds, while loans were only about $1.4 billion. Thus, Silvergate was essentially an "investment company" arbitraging between the crypto world and traditional financial markets: using its banking license and SEN to absorb deposits from crypto institutions at low or even zero interest, then buying bonds to earn the spread.

With cheap deposits and high-quality assets coexisting, everything seemed great until 2022, when two black swans arrived.

In 2022, the Federal Reserve entered a frenzied rate hike mode, causing interest rates to rise rapidly, leading to a decline in bond prices.

There is an identity in financial products: today's price * interest rate = future cash flow. The characteristic of bonds is that the amount of principal and interest repayment is already set, and future cash flows do not change, so the higher the interest rate, the lower today's price.

By the end of Q3 2022, Silvergate's securities had already shown an unrealized loss of over $1 billion.

Additionally, during the crypto bull market, the financially robust Silvergate acquired Facebook's failed stablecoin project Diem at the beginning of 2022, with a total cost of nearly $200 million in stock and cash. By January 2023, Silvergate disclosed that it had recorded a $196 million impairment charge in Q4 2022, reducing the value of the intellectual property and technology acquired from Diem Group at the beginning of last year, equivalent to the entire $200 million investment being written off.

In summary, Silvergate bought too many high-priced assets at the peak of the bubble, but under such circumstances, as long as the balance sheet does not have problems, it could land safely. However, at this moment, Silvergate's super big client FTX collapsed.

In November 2022, FTX declared bankruptcy, and under the panic, Silvergate's depositors began to withdraw funds frantically.

In Q4 2022, Silvergate's deposits fell by 68%, with withdrawals exceeding $8 billion, which is what we commonly refer to as a bank run.

A liquidity crisis ensued, and to cope with depositors' redemptions, Silvergate had no choice but to either borrow money or sell assets.

First, Silvergate was forced to sell the high-priced securities it had previously purchased in Q4 2022 and January of this year to gain liquidity, resulting in approximately $900 million in securities losses, equivalent to 70% of its equity.

Additionally, Silvergate obtained some cash by borrowing $4.3 billion from the Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco, a government-chartered institution primarily engaged in providing short-term secured loans to banks in need of cash.

The subsequent events are well-known; on March 9, Silvergate Bank announced its liquidation, stating that it would orderly and voluntarily wind down operations according to applicable regulatory procedures and would fully repay all deposits.

The Crisis of Silicon Valley Bank

If you understand the crisis of Silvergate Bank, then the liquidity crisis of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) is almost the same, except that SVB's scale and influence are larger.

Silicon Valley Bank has always been one of the most popular financial institutions among tech and life sciences startups in Silicon Valley. Once Silicon Valley Bank collapses, it will inevitably impact various startups, leading to a dual crisis in technology and finance.

The trigger event was that SVB sold $21 billion in bonds in a "fire sale," resulting in an actual loss of $1.8 billion, and thus SVB announced it would raise $2.3 billion through stock sales to cover the losses related to the bond sale.

This immediately frightened various venture capital firms in Silicon Valley.

Peter Thiel's venture capital fund, Founders Fund, directly advised the companies it invested in to withdraw their funds from Silicon Valley Bank; Union Square Ventures told its portfolio companies to "keep only the minimum amount of funds in SVB's cash accounts";

Y Combinator CEO Garry Tan warned its invested startups that the solvency risk of Silicon Valley Bank is real and hinted that they should consider limiting their exposure to lenders, preferably not exceeding $250,000;

Tribe Capital advised many portfolio companies: if they cannot completely withdraw cash from Silicon Valley Bank, they should also withdraw some funds.

Thus, a bank run ensued, and Silicon Valley Bank fell into a deeper liquidity crisis.

Let's analyze its assets and liabilities.

- Liabilities: Previously, due to the low interest rates in the entire money market, SVB attracted a large amount of deposits with a 0.25% deposit rate. Coupled with a good performance in the tech venture capital and IPO markets over the past few years, SVB's balance sheet also saw rapid growth, jumping from $61.76 billion in 2019 to $189.2 billion by the end of 2021.

However, now the tech venture capital market has become bleak, especially the IPO market has been very quiet over the past year, leading to a continuous decline in SVB's deposits. For depositors, directly purchasing U.S. Treasury bonds is a more cost-effective choice.

- Assets: Like Silvergate Bank, when there were a large number of deposits and unable to release funds through traditional lending methods, SVB also chose to purchase MBS and other bonds. The key issue is that it did not just buy a little, but nearly "went all in."

When interest rates were low, large U.S. banks still placed more deposits in government debt, accepting lower yields during uncertain economic times. Silicon Valley Bank thought interest rates would remain low for a long time, and to achieve higher yields, it invested most of its deposits into MBS.

By the end of 2022, SVB held $120 billion in investment securities, including a $91 billion mortgage-backed securities portfolio, far exceeding the total loan amount of $74 billion.

According to publicly available information from SVB, the $21 billion bond investment portfolio it sold had a yield of 1.79% and a duration of 3.6 years. In comparison, on March 10, the yield on 3-year U.S. Treasury bonds was 4.4%.

As interest rates soared, the decline in bond prices would lead to losses for Silicon Valley Bank.

SVB's $91 billion bond portfolio held to maturity is now worth only $76 billion in market value, equivalent to an unrealized loss of $15 billion.

SVB CEO Greg Becker stated in a media interview: We expected interest rates to rise, but we did not anticipate it would be this much.

Overall, the dilemmas faced by Silvergate and SVB mainly stem from misjudging the pace of the Federal Reserve's interest rate hikes, leading to erroneous investment decisions. Going all in on bonds may feel good for a moment, but the dollar rate hikes are hard to end.