a16z: It is the Web3 applications that need regulation, not the protocols

Original Title: “a16z: It’s Web3 Applications That Need Regulation, Not Protocols”

Original Author: Miles Jennings

Original Translation: DeFi Dao

Many early supporters of the internet advocated for it to remain free and open forever, making it a borderless and unregulated tool for all humanity. Over the past 20 years, this vision has lost some clarity as governments have cracked down on abuses. Nevertheless, most of the foundational technologies of the internet—communication protocols like HTTP (data exchange for websites), SMTP (email), and FTP (file transfer)—remain as free and open as ever.

Governments around the world uphold the internet's promise by embracing technologies that rely on open-source, decentralized, autonomous, and standardized protocols. When the U.S. passed the Scientific and Advanced Technology Act in 1992, it paved the way for the flourishing of commercial internet without tampering with the TCP/IP computer networking protocol.

When Congress passed the Telecommunications Act in 1996, it did not interfere with how data traversed the network but provided enough clarity for the U.S. to dominate the internet economy alongside today's giants like Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and others. While no legislation is perfect, these guardrails allowed for the development of industry and innovation, enabling us to enjoy many internet services today.

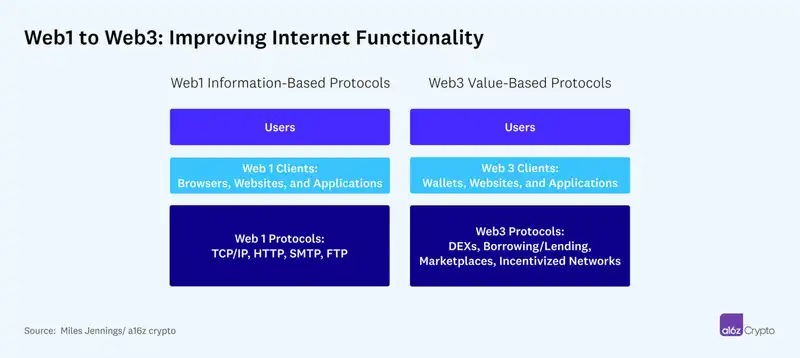

One of the main favorable factors is that the government does not regulate protocols but seeks to regulate applications, including browsers, websites, and other user-facing software, often referred to as "clients"—the means through which users access the web. This principle, which still governs the network, should extend to Web3, the evolution of the internet that will feature new applications or clients, such as web apps and wallets, as well as advanced decentralized protocols, including value exchange settlement layers implemented by blockchain and smart contracts. The question is not whether there should be Web3 regulation.

The answer to that question is obvious. Rules are necessary and welcomed. The question is, at which layer of the technology stack does Web3 regulation make the most sense?

Today, a typical web user experience may involve connecting through a regulated internet service provider and then accessing information through regulated browsers, websites, and applications, many of which rely on free and open protocols. Governments can shape this web experience by imposing access restrictions on website content or requiring compliance with privacy rules and copyright takedown requests. This is how the U.S. forced YouTube to take down terrorist recruitment videos without taking action against Dash (a video streaming protocol).

There are several reasons why regulating at the protocol level is undesirable and unfeasible. First, protocols cannot technically comply with regulations because regulations often require indefinable subjective judgments. Second, it is impractical to incorporate global regulations into protocols that vary by jurisdiction and may conflict. Third, since applications or clients can comply with higher-level technical standards, rewriting the technical foundation of the web is unnecessary and counterproductive.

Let’s elaborate on each reason in more detail.

Protocols Cannot Technically Comply with Subjective Regulations

No matter how well-intentioned a regulation is, if it requires subjective assessment, its application to protocols will be disastrous.

Take spam, for example. The hatred of spam is nearly universal, but what would the internet look like today if authorities declared that the email protocol (SMTP) facilitating spam was illegal? The definition of spam is inherently subjective and changes over time. Large companies like Google spend vast amounts trying to eliminate spam from their email applications or clients (like Gmail)—but they still make mistakes.

Moreover, even if certain authorities mandated that SMTP must default to filtering spam, malicious actors could simply reverse-engineer the filters to bypass them since the protocol is open-source. Therefore, prohibiting SMTP from facilitating spam would either be ineffective or lead to the end of email as we know it.

In Web3, we can draw an analogy between tokens and email in the context of decentralized exchange protocols (DEX). If the government wants to prohibit the use of such protocols to exchange certain tokens they deem to be securities or derivatives, they would need to articulate objective technical standards that meet this classification. But such objective classification standards are impossible. Determining whether an asset is a security or derivative is subjective and requires analysis of facts and law. Even the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission struggles with this issue.

Attempting to embed second-order subjective analysis into the foundational layer instruction set is a futile endeavor. Like SMTP, decentralized and autonomous protocols like DEX have no way to conduct subjective analysis without introducing human intermediaries, thereby negating the decentralization and autonomy of the protocol. Therefore, applying such regulations to DEX would effectively ban the protocol, completely eliminating a category of emerging technological innovation and jeopardizing the viability of all Web3.

Protocols Cannot Practically Comply with Global Regulations

Even if it were technically possible to create protocols capable of making complex and subjective decisions, doing so globally is unrealistic.

Imagine a quagmire of conflicting requirements. SMTP allows us to send emails to anyone in the world, but if the U.S. requires SMTP to filter spam, we can assume foreign governments would impose similar restrictions. Furthermore, since the definition of spam is subjective, we can also assume that government requirements would differ. Thus, even if it were technically possible to create protocols that could make complex and subjective decisions, doing so contradicts the concept of establishing a globally practical standard.

SMTP cannot possibly accommodate the ever-changing spam filter requirements of 195 countries; even if the protocol could, it would not know where users are located or how to fairly prioritize competing demands. Introducing subjectivity into the protocol undermines one of the pillars that makes protocols useful: standardization.

Rules depend on context. In Web3, what is permissible under securities and derivatives laws varies by country, and these laws are constantly changing. DEX has no way to establish a global standard for these laws, and like SMTP, there is no way to restrict access based on geography. Ultimately, if protocols are required to operate under ever-changing global regulations, they will have no chance of success.

Avoiding These Issues by Regulating Applications or Clients

Now, why it is crucial to regulate applications rather than protocols should be clear. Regulating at the application level can achieve the government’s goals without jeopardizing the underlying technology. We know this because this approach has already proven effective.

Early internet protocols remain useful over 30 years later because they are still open-source, decentralized, autonomous, and standardized. But governments can limit the information flowing through these protocols by regulating applications. Or they can protect the free flow of information, as the U.S. did by enacting Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act in 1996.

Each country can decide its own approach, and businesses operating browsers, websites, and applications within their respective jurisdictions have the ability to tailor their products to comply with these decisions.

Since the dichotomy between protocols and applications remains the same in Web3, the regulatory approach to Web3 should remain unchanged. Web3 applications, such as wallets, web applications, and other apps, enable users to deposit digital assets into liquidity pools of lending protocols, purchase NFTs through marketplace protocols, and trade assets on DEX. These wallets, websites, and applications can be regulated in every jurisdiction they attempt to provide access to, making it reasonable to require them to comply with regulations.

The first generation of the web provided us with incredible tools in the form of networks, data exchange, email, and file transfer protocols, all of which made the rapid movement of information possible. The third generation of the web enables the transfer of value to occur at this speed, with lending and asset exchange existing as native functions of this new internet. This represents an incredible public good that must be protected.

As Web3 expands from decentralized finance or "DeFi" into video games, social media, the creator economy, and the gig economy, regulating to create a fair competitive environment in these industries will become increasingly important. Weighing all the factors, the correct approach becomes particularly clear.

Applications should be regulated, not protocols.