V God 2020 Summary: How to Reassess the Operating Model of the World?

This article was published on December 28 by Block Rhythm, with the original title: "Endnotes on 2020: Crypto and Beyond"

As I write this article, I am residing in Singapore. I have spent nearly half a year in this city, which, while not long for many, is the longest I have stayed in a foreign place in nearly a decade.

After a long battle, the COVID-19 pandemic, possibly the first Boss-level pandemic humanity has faced since 1945, seems to be under control, and cities are beginning to return to normal. Although some regions still face severe challenges for the world's 7.8 billion people, there is now a glimmer of hope in the darkness. The rapid development and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines will help humanity meet this daunting challenge.

Due to various events, 2020 can be called a magical year. As "AFK" (Away From Keyboard) made people's lives more constrained and filled with challenges, the development of the internet began to become extraordinary, with mixed consequences.

Politics around the world has also taken a strange turn, and I find myself increasingly worried about the prospects of many political factions, as some politicians unhesitatingly abandon the basic principles they should adhere to for their own selfish interests. However, at the same time, some unusual dark corners are flickering with the light of hope—transportation, medicine, AI, and of course, the blockchain and crypto fields. The emergence of these new technologies may open a new chapter in human development.

Therefore, 2020 is an excellent moment to reflect on key questions: How should we reassess the way the world operates? Which perspectives, understandings, and extrapolations of the world's operations will be more useful in the coming decades, and which will become less valuable? What ways have we not seen before that have always been valuable?

In this article, I will provide some of my own answers. While my thoughts may not be comprehensive, I will delve into some interesting content. Moreover, it is often difficult to draw a clear line between what is an understanding of real changes and what is merely my long-term observations; in most cases, it is a combination of both. I believe the answers to these questions hold profound significance for both the crypto field and broader domains.

The Shift in the Role of Economics

Historically, economics has focused on tangible "goods": food, small parts of manufacturing, houses for sale, etc. Tangible assets possess some unique properties: they can be transferred, destroyed, or traded, but they cannot be replicated. It is unrealistic to have one person use an item that another person is already using; many items only hold value when directly "consumed."

The resources required to produce ten copies of a tangible item can be viewed as ten times that of producing a single copy (almost ten times, and the larger the scale, the closer it gets). But on the internet, the applicable rules are entirely different. Copying something online is simple; I can easily duplicate an article or a piece of code, even though writing an article or a piece of code requires considerable effort. However, once an article or a piece of code is completed, countless people can download and use it. They are not "consumables"; although they may be replaced by better products later, they can provide value indefinitely until they are replaced.

In the internet realm, "public goods" occupy a primary position. Of course, there are private goods on the internet, especially those existing in the form of individual scarce attention, events, and virtual assets. But overall, most goods on the internet are one-to-many rather than one-to-one. What complicates matters further is that the so-called "many" rarely maps easily onto our traditional one-to-many interaction structures, such as companies, cities, or nations; rather, these public goods are typically used publicly by widely dispersed populations around the world.

Many online platforms serving broad audiences need governance to determine their functions, content moderation policies, or other measures crucial to their user communities. However, on these platforms, user communities rarely map clearly to anything beyond themselves. When Twitter often becomes a platform for public debate between American politicians and geopolitical adversaries, how can the U.S. government govern Twitter fairly? Clearly, challenges in governance remain, and thus we need more creative solutions.

This is not merely a matter of interest in "purely" online services. While physical goods, such as food, housing, healthcare, and transportation, remain as important as ever, improvements in these goods are even more reliant on technology, and technological advancements are indeed realized through the internet.

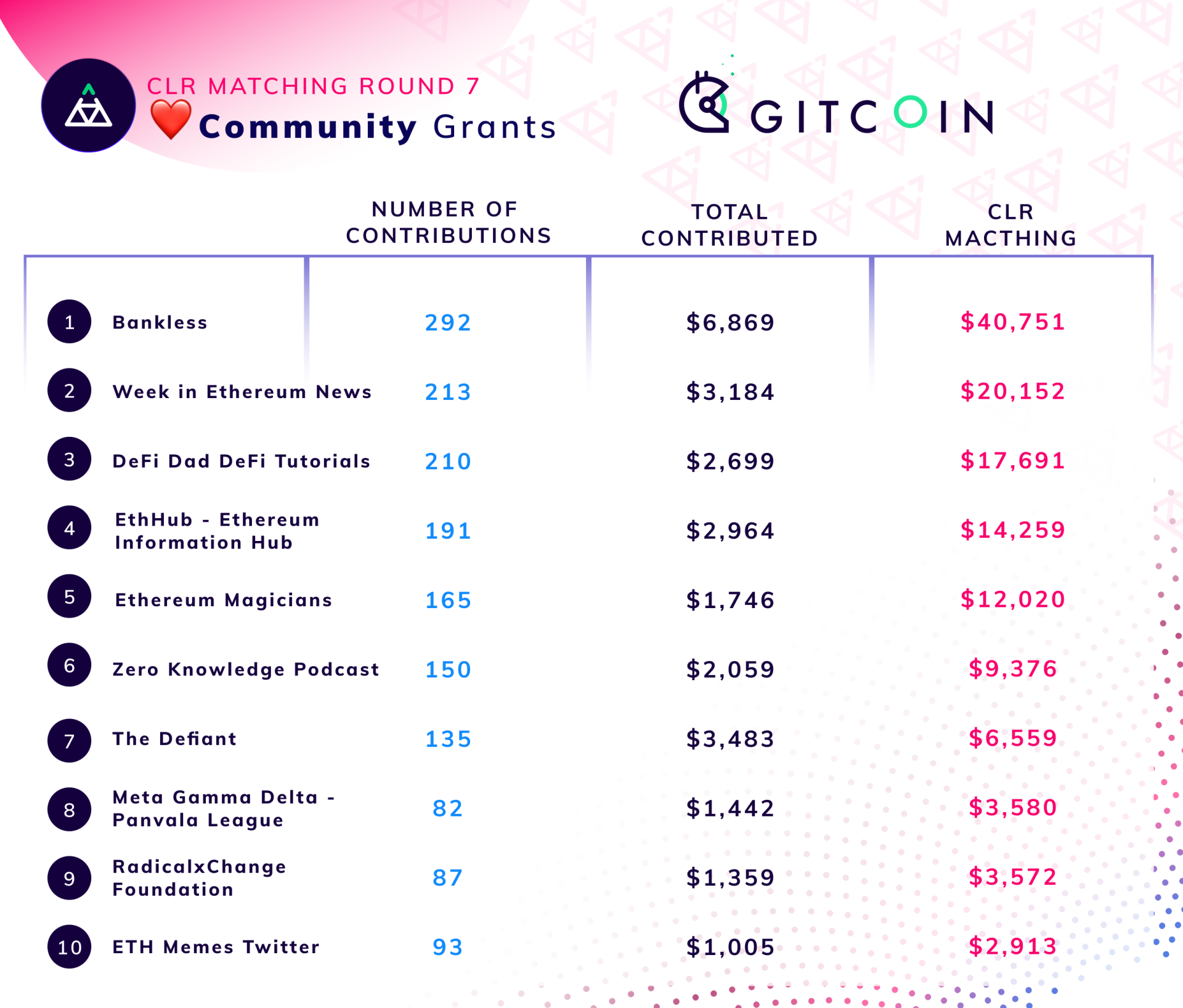

In the Ethereum ecosystem, an example of important public goods funded by the recent Gitcoin four rounds of financing. The open-source software ecosystem, including blockchain, greatly relies on public goods.

Yet, at the same time, economics itself seems to be a less powerful tool for addressing these issues. Among all the challenges of 2020, how many can be understood by observing supply and demand curves?

One way to understand what is happening is to observe the relationship between economics and politics. In the 19th century, the two were often seen as interconnected, a discipline known as "political economy." In the 20th century, they were separated. But in the 21st century, the line between "private" and "public" has once again become blurred. Government actions resemble market behaviors, while corporate actions resemble those of governments.

We see this fusion beginning to occur in the crypto space as well, with researchers increasingly focusing on governance challenges. Five years ago, the main economic issues being explored in the crypto field were related to consensus theory. This was a clearly defined, actionable economic question, so we would obtain high-quality, clear results in some instances, such as the selfish mining paper. Some subjective viewpoints (like quantifying decentralization) exist, but they can be easily encapsulated and treated separately from the formal mathematics of mechanism design.

However, in recent years, we have seen the emergence of increasingly complex financial protocols and DAOs on the blockchain, along with governance challenges within the blockchain itself. For example: Should BCH reinvest 12.5% of its block rewards to pay developer teams? If so, who decides who that developer team is? Should Zcash extend its 20% developer reward for another four years? These questions can certainly be analyzed economically to some extent, but the analysis inevitably remains in a state of coordination for a long time, with continuous adjustments; concepts like "Schelling points" and "legitimacy" are much harder to express numerically. Thus, a hybrid discipline is needed, combining formal mathematical reasoning with the softer style of humanistic reasoning.

We Want Digital Nations, but What We Get is Digitalism

Around 2014, one of the most fascinating things I began to notice in the crypto space was how quickly it started to replicate the political patterns of the entire world. I do not mean this in a broad abstract sense, such as "people are forming tribes and attacking each other," but rather in terms of the similarities, which are profound and specific.

Let me tell a story. From 2009 to around 2013, the Bitcoin world was a relatively innocent and joyful place. The community was rapidly growing, prices were rising, and while there were divergences regarding block size or long-term direction, they were mainly academic and trivial compared to the shared overarching goal of helping Bitcoin grow and prosper.

But in 2014, divisions began to emerge. The transaction volume on the Bitcoin blockchain reached 250 kilobytes per block and continued to rise, raising concerns that the blockchain usage limit might indeed reach the 1MB limit before any increase. Non-Bitcoin blockchains had previously been minor players, but from that point on, they suddenly became an important part of the field, with Ethereum arguably leading the charge.

It was precisely because of these events that the divergences, previously hidden beneath a calm surface, suddenly erupted. The ideology of "Bitcoin maximalism" posits that the goal of the crypto space should not be a diverse ecosystem of cryptocurrencies but should only include Bitcoin. This idea evolved from a niche curiosity into a prominent, angry movement. Dominic Williams and I quickly recognized its essence and dubbed it "Bitcoin maximalism." It advocates for a very slow increase in block size, regardless of how high transaction fees may rise, or even never increasing block size at all.

The divisions within Bitcoin quickly escalated into a full-blown civil war. Theymos, one of the main operators of the /r/bitcoin subreddit on Reddit, and also an operator of several other key public Bitcoin discussion spaces, took advantage of this position to impose extreme censorship, forcing his (small block) views onto the community.

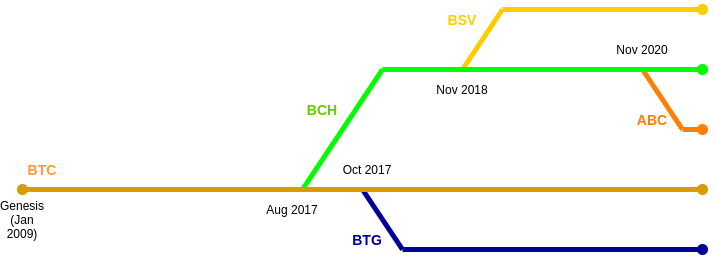

In response, large block supporters migrated to a new discussion forum, /r/btc. Some bravely attempted to resolve tensions through diplomatic meetings, including a famous diplomatic meeting held in Hong Kong, which reached what seemed to be a consensus; however, a year later, the small block faction ultimately abandoned the agreement. By 2017, the large block faction had firmly embarked on a path to failure, and in August of that year, they forked off to realize their vision on their own independent Bitcoin blockchain, which they called "Bitcoin Cash" (token BCH).

The community split was chaotic, as evidenced by the fragmentation of communication channels post-fork. /r/bitcoin was controlled by supporters of Bitcoin (BTC), while /r/btc was controlled by supporters of Bitcoin Cash (BCH). Bitcoin.org was controlled by supporters of Bitcoin (BTC), while Bitcoin.com was controlled by supporters of Bitcoin Cash (BCH). Both sides claimed to be the true Bitcoin. The outcome resembled those civil wars that often lead to a nation splitting in two, with both sides calling themselves by almost identical names, differing only in the combinations of terms like "democracy," "people," and "republic." Neither side had the capacity to eliminate the other, nor was there a higher authority to arbitrate the dispute.

The above image shows the major historical events of Bitcoin forks, with data up to 2020, not including Bitcoin Diamond, Bitcoin Rhodium, Bitcoin Private, or any other long list of lesser-known Bitcoin fork projects. However, I strongly recommend you completely ignore these forks or sell them (perhaps you should also sell some of the forks listed above, such as BSV, which is definitely a scam!).

Around the same time, Ethereum also experienced a chaotic split in the form of the DAO fork, which was a controversial solution to a theft incident involving over $50 million in Ethereum's first major smart contract application. Just like in the Bitcoin events, internal disputes arose first, although they lasted only four weeks, followed by a blockchain fork, resulting in two chains: Ethereum (ETH) and Ethereum Classic (ETC). The naming disputes were as interesting as those in Bitcoin: the Ethereum Foundation held the account ethereumproject on Twitter, while supporters of Ethereum Classic held it on Github.

Some Ethereum proponents might argue that there were very few "true" supporters of Ethereum Classic, and that the entire event was primarily a social attack by Bitcoin supporters: either support the version of Ethereum that aligns with their values or create chaos to directly destroy Ethereum. I initially believed some of these claims, but over time, I gradually realized they were exaggerated. While some Bitcoin supporters did attempt to shape the outcome according to their vision, largely, as is often the case in many conflicts, the "external interference" card was subconsciously used by many Ethereum supporters (including myself to some extent) to shield their psychological defenses, as many within our own community indeed held differing values. Fortunately, the relationship between the two projects later improved, partly thanks to Virgil Griffith's excellent communication skills, and the developers of Ethereum Classic even agreed to move to another Github page.

Infighting, alliances, factions, and coalitions with infighting participants are all visible in the crypto space. Fortunately, these conflicts are virtual and online, lacking the extremely harmful personal consequences that often accompany such events in real life.

So, what can we learn from these events?

An important insight is that if such phenomena occur in conflicts between nations, between religions, and within and between purely digital cryptocurrencies, what we are witnessing may be an indelible manifestation of human nature, something that is much more difficult to resolve than simply changing the way we organize groups. Therefore, we should expect that such situations will continue to unfold in many contexts over the coming decades. It may be harder than we imagine to distinguish the benefits and drawbacks that such situations may bring: the energy that drives us to fight also drives us to contribute.

What is Motivating Us?

An important intellectual background of the 2000s is the recognition of the significance of non-monetary motivations. People's motivations are not solely to earn as much money as possible in their work or to derive enjoyment from money in their family lives; even in work, our motivations stem from social status, honor, altruism, reciprocity, a sense of contribution, differing social views on what is good and valuable, and so on.

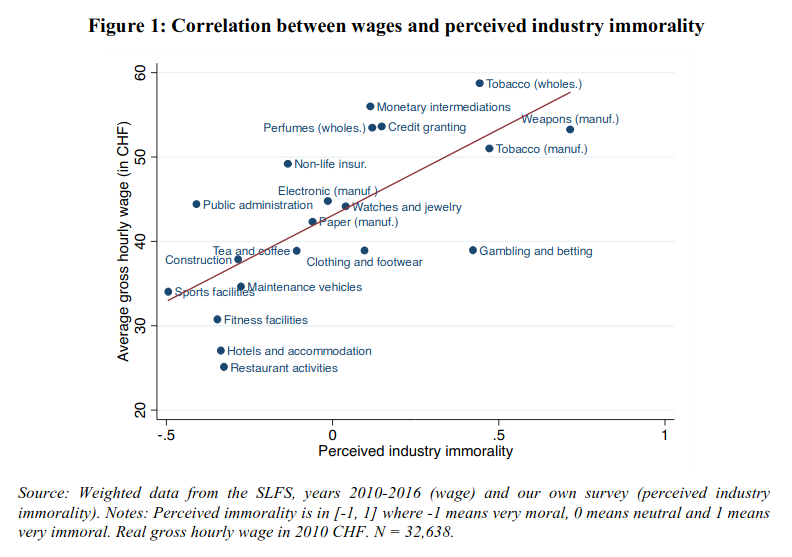

These differences are significant and measurable. For example, consider this study from Switzerland on the compensation gap for unethical work: how much extra must an employer pay to persuade someone to take a job deemed unethical?

We can see that the impact is substantial: if a job is widely regarded as unethical, you need to pay employees nearly double the salary for them to be willing to take that job. Based on personal experience, I even think that double the salary is an underestimate: in many cases, top-tier workers would not be willing to work for a company they believe is detrimental to the world, regardless of the cost.

Difficult-to-quantify "work" (like word-of-mouth marketing) also has a similar effect: if people believe a project is good, they will do it for free; if they think it is bad, they simply will not do it. This may also explain why blockchain projects that raise large amounts of money but act unscrupulously, or even just "VC chains" controlled by businesses for profit, often fail: even with a billion dollars in hand, they cannot compete with a soulful project.

That said, it is possible to be overly idealistic about this fact in several ways.

First, while the subsidies for decentralized, non-market, non-government, socially well-regarded projects are enormous—potentially reaching hundreds of trillions of dollars globally each year—their impact is not limitless. If a developer faces two choices, one earning $30,000 a year through "pure ideology," and the other earning $30 million through inserting an unnecessary token into a project for an ICO, they will choose the latter.

Second, the motivations of idealistic incentives are uneven. Rick Falkvinge's Swarmwise emphasizes the potential of decentralized non-market organizations by pointing to political activism as a key example. And this is true; political activism does not require compensation. However, longer-term, more arduous tasks—even something as simple as creating a good user interface—are not so easily driven by intrinsic motivation. Thus, if one relies too heavily on intrinsic motivation, some tasks may be overachieved while others are poorly completed or even completely neglected.

Third, people's perceptions of the intrinsic appeal of work may change, or even be manipulated.

For me, an important conclusion drawn from this is the significance of culture (and that extremely important word "narrative," which has unfortunately been ruined by influential figures in the crypto space). If a project has a high moral standing, it is equivalent to that project having double or even more funding; thus, culture and narrative are extremely powerful forces commanding value equivalent to hundreds of trillions of dollars. And this does not even cover the role of this concept in shaping our perceptions of legitimacy and coordination.

Therefore, anything that influences culture will have a tremendous impact on the world and people's economic interests, and we will see more and more various actors systematically and consciously making increasingly complex efforts. This is the dark conclusion about the importance of non-monetary social motivations: they create battlefields for the permanent and ultimate boundaries of war. Fortunately, this war is usually not fatal, but unfortunately, it is impossible to establish a peace treaty for it, as determining what constitutes a war is so subjective in cultural warfare.

The Existence of Big XXX Forms

One of the most significant debates of the 20th century was between "big government" and "big business"—the arrangements of the two differ: Big Brother, big banks, tech giants, which occasionally appear on the stage. In this environment, great ideologies are often defined as attempts to abolish various big XXX that they dislike: such as corporation-centricism, anarcho-capitalism's influence on government, and so on.

Looking back at 2020, one might ask: which great ideologies succeeded, and which failed?

Let’s take a specific example: the 1996 "Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace":

"Governments of the industrial world, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from the new home of the mind—the cyberspace. Representing the future, I ask you, the past, to leave us alone. We do not welcome you. You have no sovereignty where we gather."

And a similar spirit is echoed in the crypto-anarchist declaration:

"Computer technology is about to provide individuals and groups with the ability to communicate and interact with complete anonymity. Two people can exchange information, negotiate business, and sign electronic contracts without knowing each other's real names or legal identities. Through the widespread rerouting of encrypted packets and tamper-proof boxes, interactions on the network will be untraceable, with these encrypted packets and tamper-proof boxes achieving encryption protocols with near-perfect guarantees against tampering."

Reputation will be crucial, even more important than today's credit ratings in transactions. These developments will completely change the nature of government regulation, the ability to tax and control economic interactions, the ability to keep information confidential, and even change the nature of trust and reputation.

How have these predictions progressed? The answer is interesting: I would say they have succeeded in one aspect but failed in another.

So what has succeeded? We interact through the internet, we have powerful cryptography that even state actors find difficult to break. We even have powerful cryptocurrencies, whose smart contract capabilities were almost unanticipated by thinkers of the 1990s, and we are increasingly moving towards anonymous reputation systems through zero-knowledge proofs. What has failed? Governments have not disappeared.

So what is completely unexpected?

Perhaps the most interesting plot twist is that these two forces are often mutually reinforcing. Overall, they do not act like mortal enemies; in fact, many people within the government are seriously looking for friendly approaches to blockchain, cryptocurrencies, and new forms of cryptographic trust.

What we saw in 2020 was that big government remained as powerful as ever, but big business was also as powerful as ever. "Big protesters" were also as powerful as ever, and large tech companies were too, and perhaps soon large cryptography will be as well. It is a densely populated jungle, with an uneasy peace among many complex roles.

If you define success as the disappearance of one strong actor or even the disappearance of the kind of actor you dislike, you are likely to leave the 21st century disappointed. But if you define success more by what has happened rather than what has not happened, and you can accept imperfect outcomes, then you have enough space for everyone to feel happy.

Thriving in a Dense Jungle

So we have a world like this:

One-to-one interactions are less important; one-to-many and many-to-many interactions are more important.

The environment is much more chaotic and difficult to model with clean and simple equations. Many-to-many interactions follow strange rules, which we still do not understand well.

The environment is dense, with different categories of powerful roles forced to live closely together.

To some extent, this world is less convenient for someone like me. I have studied economics since childhood, focusing on analyzing simple physical objects and transactions, and now I have to grapple with a world where such analysis, while not entirely irrelevant, is clearly less important than before. That said, transitions are always challenging.

In fact, for those who believe that transformation is not challenging, transformation is particularly challenging because they think it merely confirms their long-held beliefs. If you are still acting according to the script written in 2009 (when the financial crisis was the most recent key event in people's minds), then you can almost be certain that you have missed some significant developments over the past decade. An ideology that has ended is a dead ideology.

In this world, blockchain and cryptocurrencies will play an important role, and the reasons are far more complex than many imagine, closely related to cultural forces and any financial power (cryptocurrency is one of the most underrated bull fields; I have always believed that gold is not highly valued, and the younger generation is realizing this, so the $9 trillion in their hands must find a new place).

Similarly, complex forces will also make blockchain and cryptocurrencies useful. It can be easily said that using centralized services can accomplish any application more efficiently. But in practice, social coordination issues are very real; people are unwilling to join a system that is even perceived as non-neutral or a manifestation of ongoing reliance on third parties, which is also a real problem. Therefore, various centralized, even consortium-based approaches claiming to replace blockchain have made no progress, while "stupid and inefficient" blockchain-based public solutions quietly advance and gain actual adoption.

Ultimately, this is a world with many disciplines, making it difficult to break it down into different layers and analyze each layer separately. You may need to switch from one analytical style to another at some intermediate level. Things happen for strange and incredible reasons, always with surprises. So the remaining question is: how do we adapt to it?