Polkadot is exploring ways to reduce inflation, but is it really feasible?

Author: Polkadot Labs

Background

On October 26, Filippo Franchini, a technical educator at the Web3 Foundation, posted a tweet on X (formerly Twitter) expressing support for burning all revenue generated from the sale of Polkadot Coretime.

Filippo Franchini believes this would be the only way to classify this revenue as "pure network income," as entering the treasury would ultimately lead to sales (and a small amount of destruction). The token needs more significant deflationary pressure, which Coretime sales can provide, although this pressure may not be substantial at first. However, this might also be another motivation to prevent them from flowing into the treasury.

At some point, due to the existence of the burn mechanism, the net inflation rate could be far below 10%, at which point there might be a vote to decide to transfer part of the sales revenue to the treasury. It has been shown that OpenGov is very efficient in implementing emergency proposals (see ideal staking rate). Filippo Franchini stated that what might be more important for him is that even if the initial sales are not substantial, burning them would create a significant positive social impact, making DOT more interesting.

This tweet sparked intense discussion among community members, with most agreeing with this viewpoint, though some argued that "this is all speculation" and that conclusions should not be drawn too early.

The next day, Filippo Franchini tweeted again, further explaining why he believes all Coretime sales revenue should be burned rather than flowing into the treasury.

He mentioned that the ideal staking rate has increased from 51% to 59%, and with the current 50% staking rate, treasury income from DOT inflation has doubled. In any case, the retention rate is primarily driven by adoption rather than purely depending on the asset's deflationary nature. However, he does not underestimate the social effects of increasing additional deflationary pressure in the Polkadot economy.

Coretime will be a tradable asset, and its sales revenue will be influenced by many factors we cannot imagine. Even if this sales revenue is negligible compared to DOT's 10% annual inflation rate (which should be another motivation not to transfer this sales revenue to the treasury), the social effects of burning this sales revenue could have a broad positive impact on the ecosystem's economy.

He also stated that ideally, Coretime sales would reduce DOT's net inflation rate, and OpenGov could intervene and change the status quo whenever necessary.

In fact, as early as mid to late July, Jonas from the Web3 Foundation initiated an RFC (request for comments) on GitHub, proposing to burn the revenue generated from the upcoming Polkadot Coretime sales.

Jonas stated that having consistent and predictable treasury income is in the interest of the Polkadot community, as volatility in inflows can be harmful, especially in cases of insufficient funding. Therefore, this RFC operates under the assumption of stable and sustainable treasury income flows, which are crucial for the stability of the Polkadot community. According to Jonas, burning Coretime sales revenue has three benefits: balancing inflation, providing clear incentives, and achieving collective value.

Earlier, in early July, Jonas proposed adjusting the current inflation model on the Polkadot forum. He believes that the current inflation model could lead to a situation where treasury funds (from inflation) could drop to zero.

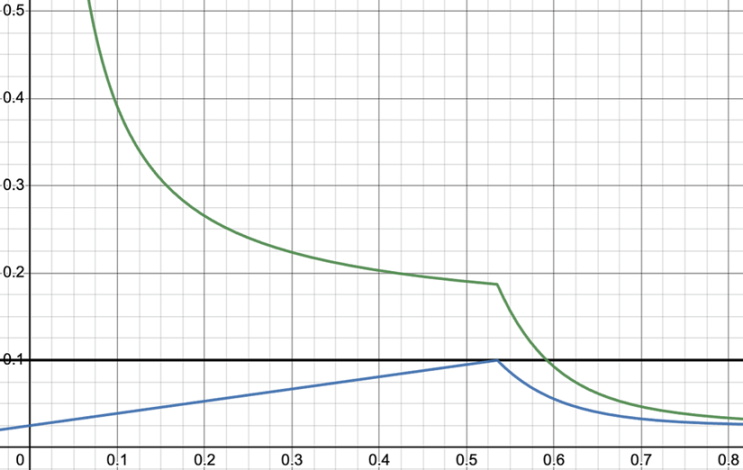

(Blue: Staker's inflation rate, Green: Staker's annual yield, Black: Total inflation rate)

Essentially, the annual inflation rate is fixed at 10%, and the distribution between stakers and the treasury is determined by the difference between the ideal staking rate and the actual staking rate. In this case, the treasury would receive 0 DOT from inflation.

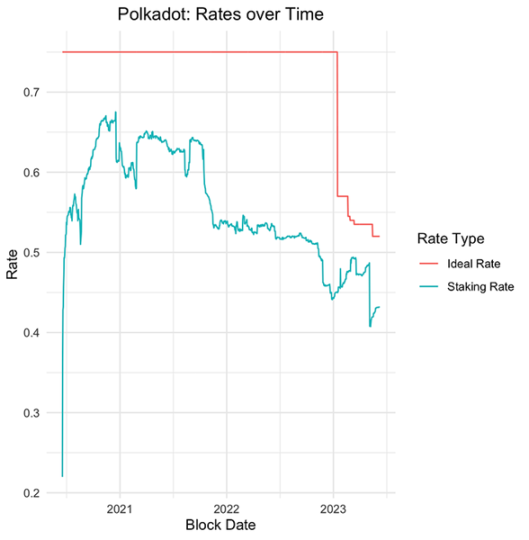

The subsequent chart depicts the historical evolution of the staking rate compared to the ideal rate:

As the gap between these two metrics narrows, the treasury's share of rewards from stakers will decrease, and it is expected that the gap between these two key metrics will further narrow in the future. This also means that the treasury's balance may struggle to support its ongoing expenditures.

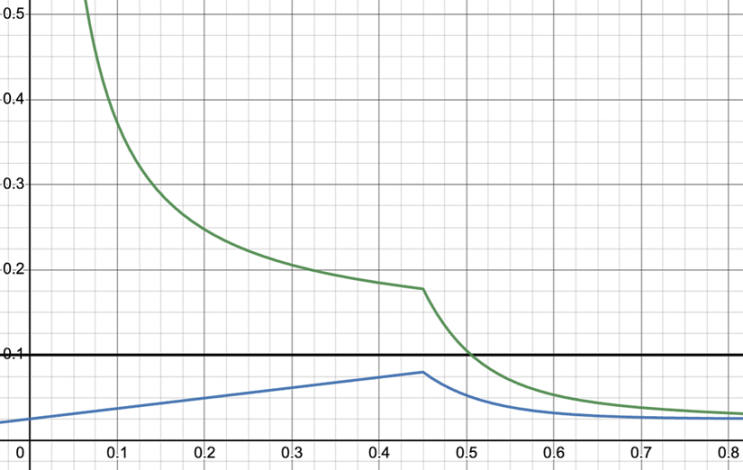

According to Jonas, to ensure the treasury operates well and has a predictable minimum inflow, we should modify the underlying model. Jonas proposed that 20% of the annual inflation be directly allocated to the treasury, while the remaining 80% would be adjusted using the current mechanism. The following diagram provides a representation of the proposed mechanism:

Since the proposed allocation reflects historical distribution, the impact of these modifications is minimal. The resulting parameters should be made public for easier adjustments in the future. Additionally, implementing this change requires a runtime upgrade and root management permissions, so extensive discussion is necessary. Once consensus is reached, the proposed changes need to be coded and incorporated into the runtime upgrade.

Perspectives on the Inflation Issue

Is adjusting the current inflation model beneficial for the entire ecosystem? Some forum members shared their views on Jonas's proposal.

Forum member lolmcshizz believes that more data is needed regarding the new treasury expenditure rates under OpenGov, as well as "future" treasury income data after the Coretime sales go live.

OpenGov has been running for some time, and after experiencing the "painful process" of approving each treasury expenditure, everyone realized this was unsustainable, so they reassessed which proposals should and should not receive funding from the treasury to determine the "true treasury operating rate." With the launch of "Polkadot 2.0," the model shifts to one where DOT pays for block space, and these DOTs will enter the treasury, potentially offsetting any deficits caused by inflation.

joepetrowski believes this is a reasonable suggestion, but as Agile Coretime develops, this mechanism can be reassessed rather than just adjusting parameters.

Since Coretime payments will be direct payments rather than locking up DOT, it can be explored whether the treasury or validators need to obtain funding through inflation.

For example, funds from Coretime payments could be 100% allocated to the treasury (i.e., purchasing Coretime could fund the network's future development). But in principle: purchasing Coretime funds the treasury → the treasury receives a good allocation → leads to more projects wanting to use Coretime (because it is of higher quality or has more services making it easier to use/integrate) → leads to those projects wanting to use Coretime obtaining DOT to purchase it → putting DOT back into the treasury.

Then, we can consider reducing inflation (but this is not the goal; as long as demand for Coretime grows more, inflation is not a problem). However, inflation should primarily fund the growth of validators, which is also necessary for providing more parallel cores. In this way, the treasury will either increase its income due to growing demand for a fixed number of cores or maintain stable prices per core as the number of cores increases.

AlistairStewart believes that Coretime revenue will initially increase slowly and suggests modifying the mechanism based on the situation.

First, the initial cost of each core is relatively low, as Gavin has promised; otherwise, existing parachain projects may have to quickly launch new models. Secondly, every time we introduce Coretime and stop auctions, we adhere to the existing lease period, so the number of cores requiring payment will gradually increase over two years. Finally, improvements in the parachain system will provide us with more cores, but who knows if demand will match this?

AlistairStewart states that we cannot predict the situation two years from now; inflation provides a more predictable funding source for the treasury and stakers. Therefore, he suggests implementing such reforms first and then considering whether to burn Coretime revenue. A few years later, if we can lower the inflation rate and have high demand for cores, we might even see deflation.

Polkalytics researcher Alice und Bob believes the proposal is still somewhat inappropriate regarding verification issues.

He states that we should not immediately conclude that we need to increase treasury income but rather establish a framework for how much inflow and outflow is desirable during a market cycle. Because in a prosperous market, the outflow of treasury funds could very well decrease, and the problem could completely disappear or begin to manifest in different ways. Only after we clarify this issue and have a concept of the budget should we turn to changing the system's parameters.

As a feasible compromise, Alice und Bob suggests deriving minimum and maximum parameters for inflow and outflow through discussion, and then arriving at a model that accommodates these parameters.

Other forum members also offered insightful suggestions. Although everyone's ideas differ, most believe that more data analysis is needed before advancing this proposal. These discussions are very necessary, as they can help us gain a deeper understanding of the operational mechanisms and optimization directions of the Polkadot ecosystem. Strengthening communication with the community before making any significant changes is also essential to gather more feedback and suggestions.

Several Issues Involved in Polkadot's Inflation

From the above situation, we can see that Polkadot's inflation involves multiple aspects.

First, Polkadot's inflation rate affects the yield from staking and the amount of funds flowing into the treasury. On the other hand, the current expenditure of treasury funds is calculated based on the dollar amount requested for each proposal divided by the current DOT price, determining how many DOTs need to be sponsored for each proposal. Therefore, when the DOT price is relatively low, it leads to a faster consumption of DOTs in the treasury. This triggers a series of chain reactions, with rapid consumption of treasury funds making the review of many treasury proposals stricter, resulting in a large number of proposals being rejected and many developments stagnating.

While raising the review standards for treasury proposals is fundamentally a good thing, the actual situation is not as ideal as imagined. Many voters do not fully understand the specifics of the proposals and simply vote against them because they believe the proposals are too costly. Such sentiments can severely hinder the normal operation of Polkadot governance.

Secondly, the community generally believes that Polkadot's inflation rate is too high, which can also significantly affect the psychology of holders who do not participate in staking. Many may think that high inflation devalues their DOT, leading them to sell DOT and causing the price to drop.

Moreover, excessive inflation can also impact the development of ecological applications. High inflation makes staking rewards very high; currently, DOT's staking rewards have exceeded 15%. Such a return rate far exceeds that of some mature business models (such as lending, AMM, etc.), causing the rewards offered by projects in ecological applications to lose sufficient attractiveness, with funds being more inclined to participate in DOT staking, which is not conducive to the development of ecological applications.

In addition, Polkadot's slot auctions previously involved locking up DOT to participate in bidding for the right to use Polkadot's block space. However, with Gavin's proposal for Polkadot 2.0, the slot auctions will shift to the buying and selling of Coretime, but there is currently no definitive revenue from Coretime sales, leading to discussions on how to handle this portion of DOT. Therefore, recent discussions on Coretime revenue aim to address the issue of excessive inflation in Polkadot to some extent.

Based on Filippo's responses on Twitter and recent interviews with PolkaWorld, it is clear that he has his understanding of Polkadot's inflation issue. He believes that inflation in Polkadot is not the primary concern for everyone. He considers Polkadot's inflation important, stating that Polkadot is not like developed countries; it resembles a developing country that is rapidly growing, thus requiring a faster growth rate. The GDP growth rate of developing countries can also reach 10%, so he believes that Polkadot's 10% inflation rate is not excessive. Currently, a 10% inflation rate not only incentivizes network participants but also constitutes the treasury, allowing for funding many projects.

He believes that the risks of lowering inflation could be significant, and reducing inflation too much could hinder Polkadot's growth. Therefore, this issue needs to be addressed carefully. He thinks people should not worry about inflation. Bitcoin is an example of gradually decreasing inflation, with its growth primarily coming from adoption. Polkadot's Coretime revenue could potentially be entirely burned through OpenGov, and he is very confident that this proposal will pass. He believes that Coretime revenue represents true network income, and burning all Coretime revenue will create a narrative of token deflation for Polkadot.

Our Perspective

The author believes there are many misconceptions in Filippo's viewpoint.

First, the fact that the GDP growth rate of developing countries can reach 10% does not mean that a 10% annual inflation rate for Polkadot is reasonable; the two cannot be conflated. The situation where the GDP growth rate of developing countries reaches 10% can be understood as a balloon expanding due to an increase in gas inside, compared to before, increasing by 10%. In contrast, Polkadot's annual inflation rate of 10% is akin to a rigid container forcibly expanding by 10% while the total amount of gas inside remains unchanged. Although the container appears to have expanded by 10%, the density of the gas inside has correspondingly decreased by 9.1%.

The former represents a bottom-up growth driven by economic strength, while the latter is a top-down forced expansion, naturally diluting the corresponding value. Therefore, it is necessary to rethink the question of whether "a 10% inflation rate for Polkadot is reasonable."

Secondly, Filippo believes that the risks of lowering inflation could be significant, and reducing inflation too much could hinder Polkadot's growth. His concern mainly revolves around the treasury running out, as lowering Polkadot's inflation would reduce the DOT assets entering the treasury. However, as we previously analyzed, inflation can lead to lower prices, thereby accelerating the consumption of DOT in the treasury. Creating an expectation of appreciation for Polkadot will naturally slow down the consumption rate of the treasury.

Furthermore, treasury income can also be increased by adjusting the optimal staking rate, and Coretime revenue can be funneled into the treasury. However, increasing prices has the added benefit of boosting user confidence in Polkadot. Our previous survey indicated that over 90% of respondents were dissatisfied with the current inflation rate, so the negative sentiment caused by high inflation far outweighs the benefits of lowering inflation.

Finally, Filippo believes that burning all Coretime revenue, even if the initial sales are not substantial, would create a significant positive social impact, making DOT more interesting. However, the author believes that while this may create a narrative of increased deflation for Polkadot and generate some bullish sentiment, such sentiment cannot be sustained, and on-chain data can clearly show the extent of the deflationary effect of burning all Coretime revenue.

Based on the current situation of Polkadot's slot auctions and Gavin's promise that the initial Coretime will be very cheap, it is likely that for a period, Coretime revenue will be minimal and will not have a direct effect on reducing the inflation rate. "It has deflated, but not by much."

How Should Coretime Revenue Be Allocated?

Returning to the topic of this discussion, how should Coretime revenue be allocated?

At least Filippo and others believe it should all be burned, as this approach is simpler and creates a narrative of "all network income from Polkadot being burned," without affecting Polkadot's overall inflation rate, ensuring sufficient DOT flows into the Polkadot treasury.

However, the author believes that to answer this question, we need to further consider what the goal of this issue is. Is it merely to add a burning mechanism to Polkadot, creating some expectations of deflation? The author believes there is a larger question at stake: how should Polkadot's inflation rate be adjusted? The issue of Coretime revenue allocation is merely a subset of this larger question, and we should approach this smaller issue with the aim of solving the larger problem.

Therefore, the author believes that simply burning all Coretime revenue is a lazy approach, as it may not effectively address Polkadot's inflation issue. Regarding how to adjust Polkadot's inflation, the author has detailed explanations in the chapter "Improving Inflation: Dynamic Adjustment of Inflation" in the Ten Thousand Word Strategic Report | How Should Polkadot Overcome Growth Dilemmas, and What Is the Future Path?. Here, I will directly quote the conclusions:

- Polkadot should adjust the total inflation rate from 10% to 5%.

- All Coretime revenue should be funneled into the treasury.

- The treasury should burn 1% every 24 days, and this fixed rate can be changed to a dynamic rate, ultimately controlling Polkadot's inflation rate within ±2%.

The author believes that Coretime revenue should not be directly burned but should first be funneled into the treasury and then burned collectively through the treasury. This is because Coretime revenue can fall into three scenarios: one scenario is that the revenue is too low, and burning it all would not directly adjust the inflation rate; another scenario is that the revenue is too high, leading to excessive burning of DOT, which could make DOT more scarce and hinder its widespread use; the final scenario is that the revenue is moderate, allowing Polkadot's inflation rate to remain within a reasonable range.

If we only burn all Coretime revenue, there will inevitably be proposals in the future to adjust the burning ratio, changing from total burning to partial burning to make Polkadot's inflation more moderate. Thus, we can see that the burning ratio of Coretime revenue needs to be adjusted, and on the other hand, the treasury also burns once every 24 days. Therefore, if we want to adjust Polkadot's inflation, we need to balance both parameters simultaneously. This will make it more complex for Polkadot to adjust in the future.

However, if we funnel all Coretime revenue into the treasury and only adjust the ratio burned by the treasury every 24 days, we can control Polkadot's inflation with a single parameter. This would make it easier for us to intuitively adjust Polkadot's inflation and respond to more variables.

Postscript

What do you think about the allocation of Coretime revenue?

Do you accept Filippo's viewpoint: to directly burn all Coretime revenue and create a narrative of "increased burning" for Polkadot, although the immediate deflationary effect may not be very noticeable? While this approach is simpler, the results produced in the future may become complex and more difficult to handle with various variables.

Or do you accept the author's viewpoint: to funnel all Coretime revenue into the treasury, reduce the overall inflation rate from 10% to 5%, and finally control the ultimate inflation rate within ±2% through dynamic adjustments to the treasury's burning ratio every 24 days? Although this process is more complex, the results produced in the future will be simpler and can handle more complex variables.

Or perhaps you have your understanding. Regardless, we hope everyone can actively participate in important discussions about Polkadot, such as sharing your views on the allocation of Coretime revenue in the GitHub post or participating in discussions about the economic model in the Polkadot forum.

We hope everyone can express their opinions and contribute to the DOT they hold. Step by step, we can reach a thousand miles.