a16z: Scientific Governance Measures of "Machiavellianism DAO"

Original Title: Machiavelli for DAOs: Designing Effective Decentralized Governance

Original Author: Miles Jennings, General Counsel at a16z crypto

Translation by: Babywhale, Foresight News

Web3 should triumph over Web2 because Web3 can achieve decentralization, which will reduce censorship and promote freedom. Freedom makes it possible to oppose power, and opposition to power drives greater progress. But first, we need to address the issue of decentralized governance.

As decentralized governance is still in its early stages, many Web3 protocols and DAOs are still exploring solutions to the problems that arise in decentralized governance. As someone who closely follows decentralized governance practices across Web3 (including how to influence decentralization and how to incorporate it into various decentralized models), I believe that applying Machiavellian principles to decentralized governance in Web3 can address current shortcomings, as Machiavelli's philosophy developed from a pragmatic understanding of social power struggles at the time. These social power struggles are similar to those experienced by protocols and their DAOs, which often have ambiguous, volatile, or inefficient social hierarchies.

In another article, I outlined four Machiavellian principles as guidelines for designing stronger and more effective decentralized governance, or "Machiavellian" DAOs: embrace governance minimization; establish a balanced leadership tier that is always challenged by opposition; provide pathways for continuous change in the leadership tier; and reinforce the sense of accountability among the leadership team. In this article, I will share the factors, strategies, and tactics that need to be considered when creating "Machiavellian DAO" guidelines.

The strategies and tactics I propose may not be suitable for all DAOs, as these approaches introduce inefficiencies and friction into decentralized governance, making them potentially unsuitable for highly dynamic and evolving systems or civic-oriented systems. However, for those protocols that are in development and focus on maintaining credible neutrality while emphasizing economic growth, such as the hypothetical Web3 marketplace protocol "Blockzaar" that I use as an example in this article, the benefits of increased friction may far outweigh the costs.

Two Steps to Implement Before Designing a DAO

Before sharing design principles, it is crucial to identify who the stakeholders are in the ecosystem. Once these different stakeholders are identified, the DAO can determine what their intrinsic motivations are, which is a prerequisite for balancing the power of these stakeholders.

After the following two preliminary steps, builders can implement the next four Machiavellian design principles.

Step 1: Identify Protocol Stakeholders

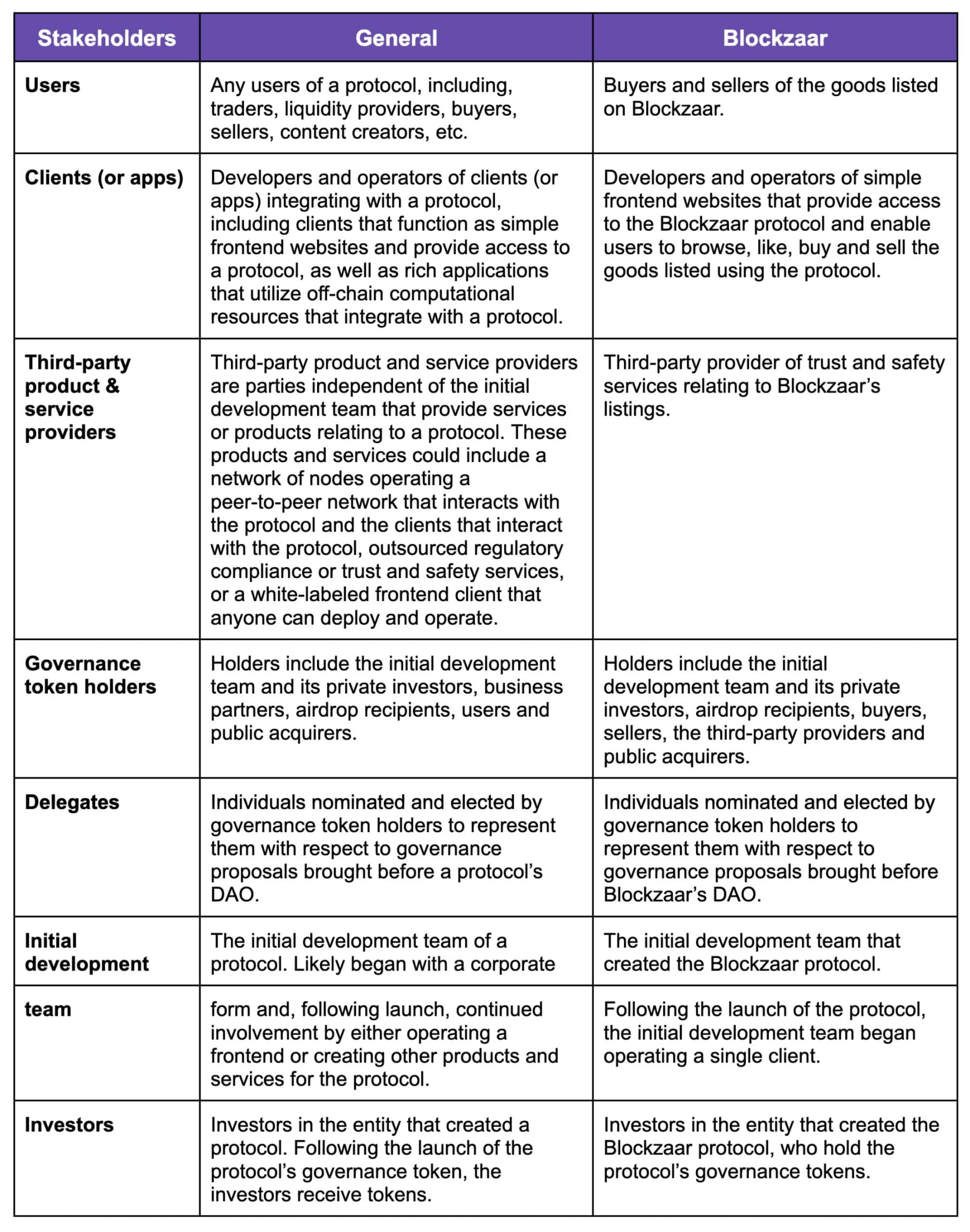

Stakeholders in a Web3 protocol include many different participants, such as users, applications (or clients), third-party product or service providers, governance token holders, representatives, initial development teams, and investors:

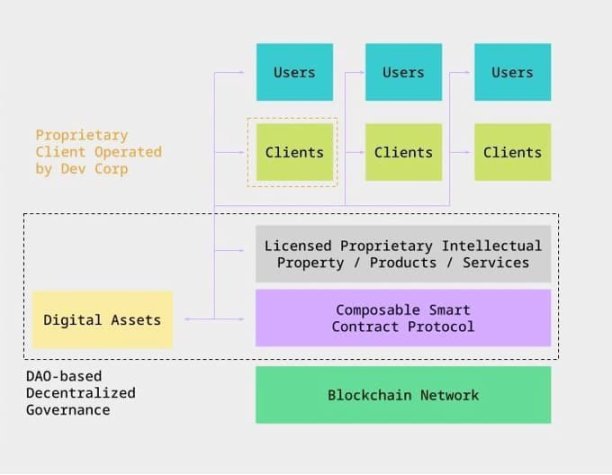

Step 2: Understand the Incentive Structure

The more active stakeholders (as opposed to passive investors) there are—who are economically motivated to see the protocol grow and develop—the more parties there are available to effectively manage the protocol. This is why Web3 systems that encourage the creation and operation of independent clients/applications (client layer) on top of shared smart contracts/blockchain infrastructure (protocol layer) and encourage independent third parties to create off-chain products and services for stakeholders within the ecosystem (third-party layer) are best suited to leverage Machiavellian structures. (See here for a discussion of open decentralized models.)

Here is an ecosystem model using these two incentive structures:

The goal of these incentive schemes is to make independent third parties profitable, allowing them to operate clients as independent businesses on top of the protocol while also creating tools and other shared intellectual property and services for protocol clients and users. These elements help facilitate the decentralized economic prosperity of the protocol and provide fertile ground for designing more effective decentralized governance by giving independent participants vested interests in the success of the decentralized economy.

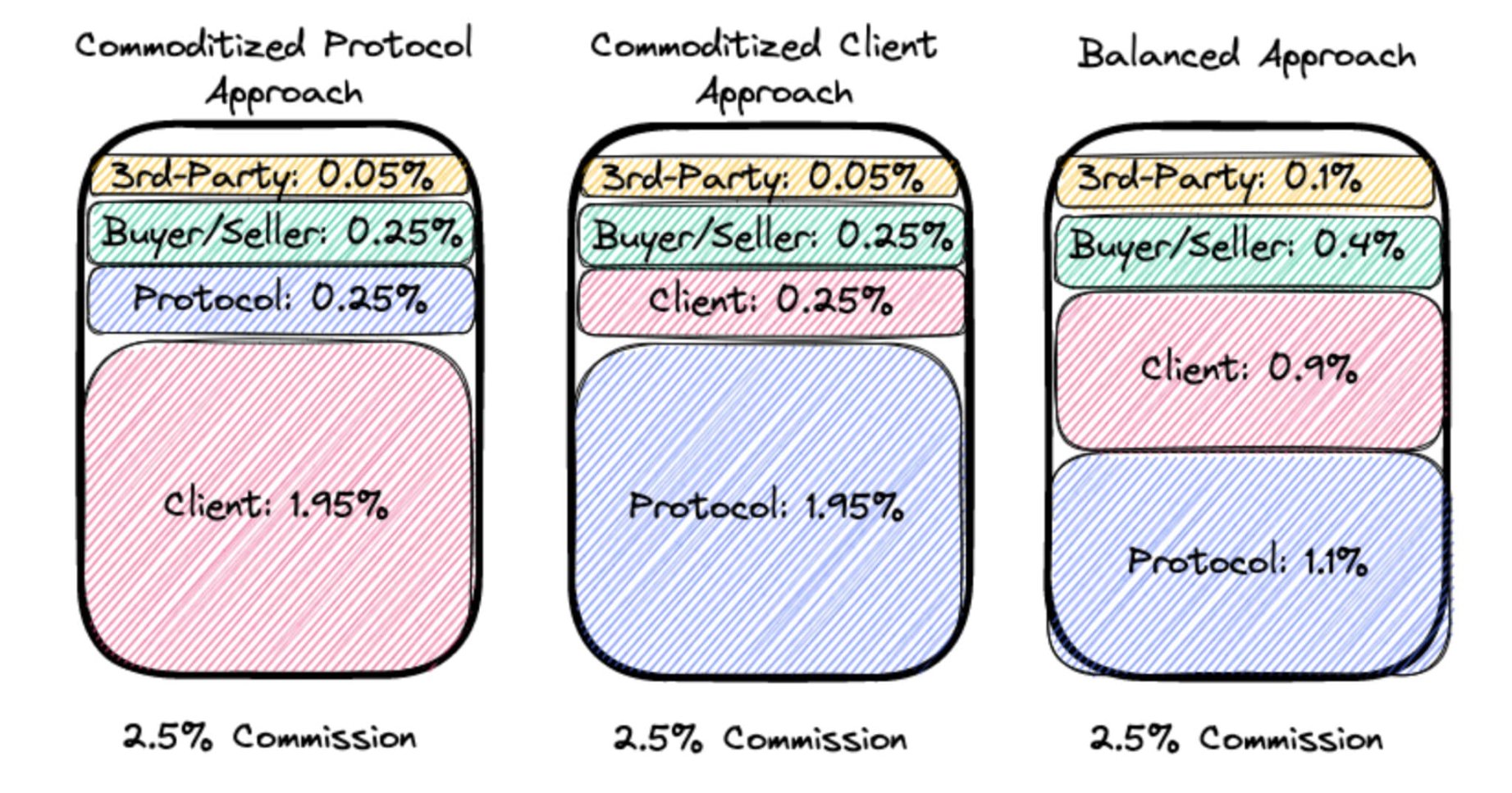

When designing incentive mechanisms, DAOs must balance the interests of the protocol/DAO (including token holders) with the interests of other stakeholders in the system (users, client operators, and third-party product and service providers). Token holders may not support the commercialization of the protocol layer (where all value goes to users, clients, and third-party product and service providers) because it would deprive them of economic benefits. This commercialization also contradicts the goal of accumulating network effects for the protocol.

At the same time, commercialization of the client layer—where all value goes to the protocol (also known as "fat protocols")—is unlikely to produce a rich client ecosystem, as builders cannot profit from developing clients. Both extremes jeopardize the decentralized economy of the entire system. Therefore, many ecosystems should adopt a more balanced approach; to illustrate this, here is a very simple incentive scheme using "Blockzaar" as an example of a hypothetical Web3 marketplace business:

- The purpose of the protocol is to incentivize buyers to purchase products; incentivize sellers to sell products; incentivize client operators to maintain such clients; and incentivize third-party service providers to develop and provide products and services to the ecosystem;

- The benefits generated by the protocol are a 2.5% commission on all buy-sell transactions, which can be distributed to stakeholders through the allocation of such transaction revenues or the distribution of governance tokens;

- Buyers and sellers can only benefit when participating in buy-sell transactions. Client operators can only benefit when transactions are completed through their clients. Third-party product and service providers only benefit when transactions are completed using clients that utilize their trusted and secure services.

The benefits represented by the commissions earned by Blockzaar can be distributed among stakeholders as follows:

As shown in the diagram, of the 2.5% commission, 1.1% goes to the protocol, 0.9% goes to the client that initiated the transaction, 0.4% goes to the buyer or seller, and 0.1% goes to the third-party service provider. Thus, both token holders (through benefits generated by the protocol) and other stakeholders are rewarded for the execution of transactions.

Why reward stakeholders? There are two additional considerations:

First, a balanced incentive structure may not only be feasible but may be necessary for certain systems. Regulatory actions in the U.S. have clearly indicated that systems facilitating regulated activities need to find ways to comply with regulatory requirements. In the vast majority of cases, it is impossible to design compliance into the protocol itself, so this compliance needs to be implemented at the interaction points between users and the protocol, which is the client layer of the protocol. Therefore, operators of protocol clients that facilitate regulated activities need to generate revenue from the operation of the clients to cover compliance costs. Abandoning compliance is not an option: it not only puts client operators at risk but also exposes the protocol's DAO to legal risks from collecting funds from illegal activities.

Thus, in cases where the protocol facilitates regulated activities, the "fat protocol theory" does not hold, and a balanced approach must be taken.

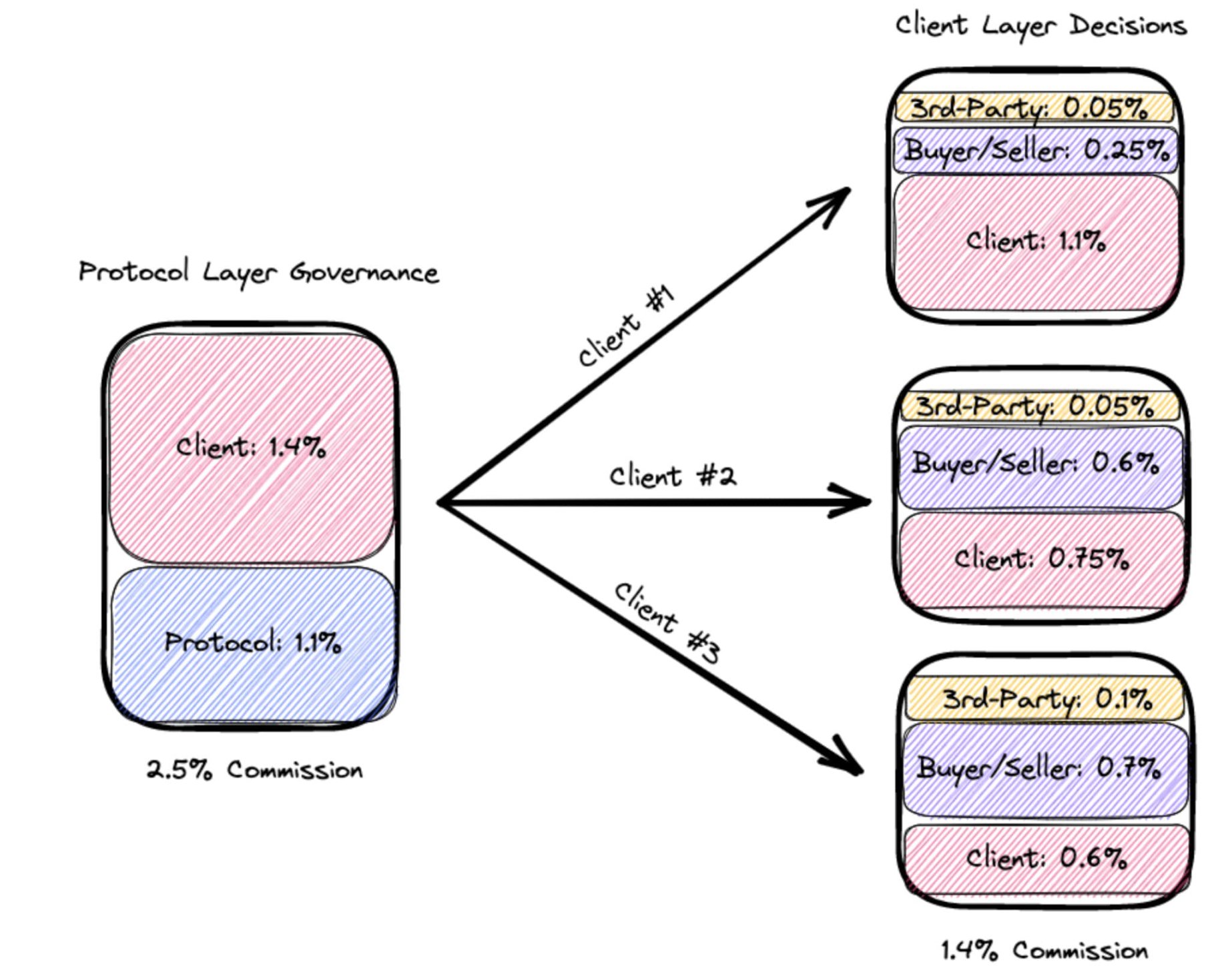

Second, in any decentralized model that incentivizes a strong client layer, a power balance among clients must be achieved. If a single client captures too many users, its position in the client layer will jeopardize the decentralization of the system. Therefore, the design of the protocol must be able to withstand the risk of being dominated by clients. To this end, DAOs can impose controls on clients that exceed a predetermined client dominance threshold (such as 50% of user transaction volume). To avoid manipulating such mechanisms to censor certain clients, these mechanisms should be as autonomous as possible and set upper and lower limits on the client dominance threshold. For example, for Blockzaar, this mechanism would only be triggered if a client's transaction volume exceeds 50%, which would reduce its commission distribution from 1.4% to 1.0%, with the 0.4% difference going to the protocol.

Four Principles for Designing Machiavellian DAOs

Now that we understand the interactions between protocol stakeholders and the incentive structure of the protocol, the DAO of the protocol can be designed according to the four principles derived from Machiavellian principles.

Principle 1: Governance Minimization

Machiavellians believe that organizations tend toward authoritarian leadership, which ultimately discriminates to perpetuate its own privileges and power. This suggests that DAOs should prioritize governance minimization to protect their credible neutrality as much as possible. In other words, since every human decision that affects the protocol may discriminate against stakeholders and harm the ecosystem's credible neutrality, such subjective human decisions should be minimized.

The general consensus on governance minimization is that protocol governance should be reduced to three categories of decisions that must be made:

- Complex parameter settings, such as collateral ratios in DeFi lending protocols;

- Fund management, such as fund diversification, grant programs, including funding for public goods;

- Maintenance and upgrades of the protocol, including replacing oracles, deploying upgraded smart contracts, etc.

The number and scope of decisions for specific DAOs in any of the above categories will largely depend on the type of protocol they manage.

It is certain that as Web3 protocols become increasingly complex, the number and scope of decisions will also increase. However, this does not necessarily mean that decentralized governance at the protocol layer needs to become equally complex. On the contrary, DAOs can leverage decentralized models of incentives to address this trend and further promote governance minimization.

In particular, DAOs can safeguard their credible neutrality by "pushing" many governance decisions to the client layer and/or third-party layer. For example, decisions that only affect the client-user relationship can be made by individual operators of the clients. While these operators can use decentralized governance to manage their clients, the inefficiencies of decentralized governance may render it impractical.

Fortunately, using decentralized governance at the client layer is likely unnecessary, as users do not directly participate in governance at the client layer but can influence it by either accepting the decisions of individual client operators and continuing to use those clients or by switching to different clients to circumvent those decisions. Similarly, third-party product and service providers can offer products and services with different features and prices, allowing clients and users to choose according to their preferences.

Thus, a strong client layer and third-party layer can reduce the need for decentralized management while increasing user choice.

This is similar to the "fork-friendly" environment advocated by Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin and others, which is a remedy for the decentralized governance problem, only it extends beyond the protocol layer. Essentially, each client is a fork of other available clients; each third-party product and service is a fork of other available products and services. This dynamic promotes competition, allows for rapid experimentation, provides users with more diverse choices, and maintains the credible neutrality of the protocol layer.

For example, in a Web3 social network, if a client operator wants to remove all hate speech from their client, users can either accept this censorship by continuing to use that client or circumvent it by switching to a client that has not taken such measures. But this censorship does not apply to the protocol layer, which will remain neutral regarding speech. This is preferable to the current content moderation methods of Web2, where users often do not even know which speech is restricted, by whom, or why. The issues of Web2 social media and the arbitrary, subjective decisions of a few strongly point to a better solution: Web3 protocols with governance minimization.

Forking at the client layer and third-party layer also avoids several key drawbacks that hinder forking at the protocol layer, including the fragmentation of liquidity when forking DeFi protocols; or the fragmentation of user bases/audiences in Web3 social protocols. Forking at the protocol layer ultimately consumes the network effects generated by the protocol, making it undesirable for protocol developers and early adopters. For Blockzaar, governance minimization and the related concepts I share can be achieved by the DAO as follows:

Complex Parameter Settings. For the simplest version of Blockzaar, the only parameter that could be changed by the DAO might be the commission rate applicable to transactions and how that commission rate is distributed between the protocol layer and the client layer. As shown below, the commission ratio among clients/users/third-party product and service providers can be "pushed" to the client layer, where each client can decide how to allocate the commissions earned from the protocol among its users and third-party product and service providers:

Fund Management. The simplest governance design for Blockzaar may still authorize the DAO to participate in fund management activities. This would include creating grant programs, funding the development of public goods within the market ecosystem, and providing other third-party products and services to clients and users.

Protocol Maintenance and Upgrades. The simplest governance design for Blockzaar may still authorize the DAO to maintain and upgrade the protocol. This would help keep pace with competition, especially considering the rapid technological iterations in Web3.

Overall, if Blockzaar can achieve governance minimization, it can significantly limit the number of decisions that need to go through decentralized governance processes, thereby significantly reducing the governance burden on the protocol. Nevertheless, the protocol can still achieve a degree of variability and experimentation by fostering a robust ecosystem of incentivized clients and third-party products and services.

Principle 2: Balanced Leadership Tier

Given the above and the increasing complexity of Web3 protocols, even the most extreme minimization of governance is unlikely to eliminate all human factors. Therefore, DAOs must take further measures to ensure that the decisions they must make can be made effectively. For example, in the case of Blockzaar, if a new version of the protocol is released, the DAO will need to decide whether to accept it.

Considering that most political systems tend toward authoritarian leadership (as Machiavellians have observed), DAOs should seek to establish a leadership "tier" for the ecosystem to handle the remaining governance matters more effectively. But the key is to design checks and balances on the power of any leadership tier so that any emerging leaders are always subject to public opposition.

While DAOs can attempt to overcome authoritarianism using non-token-based voting designs (such as soulbound tokens), the principles summarized by Machiavellians based on observations of contentious politics suggest that such designs are unlikely to succeed in the long run. Even if "soulbound tokens" can eliminate the different rights that token holders have due to their ownership of tokens, token holders in DAOs using this method are likely to coalesce into new groups based on new property rights and new class distinctions. Therefore, while soulbound tokens can mitigate the vulnerability of DAOs to attacks, they cannot eliminate authoritarianism.

Establishing a system of checks and balances is a better option. Fortunately, incentivized decentralization provides fertile ground for exploring other tools to balance the power of leadership tiers. Below, I will share a potential DAO design that adopts a bicameral governance layer—unlike the U.S. Congress's House of Representatives and Senate.

Stakeholder Council

If a protocol can incentivize a strong ecosystem composed of clients, third-party products, and service providers, all of which operate independently, it is reasonable that these individuals have vested interests in the governance of the protocol. Their livelihoods may depend on the protocol's survival. Additionally, the most active users of the protocol may also be vested stakeholders in its governance, especially if their usage is related to the businesses they operate.

Given their vested interests, these stakeholders may be best suited to participate in the decentralized governance of the protocol. However, under the current token-based voting forms, these stakeholders are unlikely to have sufficient agency in decentralized governance, thereby minimizing the potential to promote genuine stakeholder capitalism in these ecosystems.

By using non-token voting, providing stakeholders with their own stakeholder council can overcome this challenge. In particular, non-transferable NFTs (also known as soulbound NFTs) can be granted to certain individuals in each constituency, giving these holders the right to propose and vote on issues facing the DAO.

When designing any such leadership tier, the DAO should:

Decentralize the power of the leadership tier sufficiently so that no individual or related group can be said to control the DAO. First, according to U.S. securities law, establishing a leadership tier may have negative implications. The leadership tier should be composed of multiple members elected from each constituency by the DAO.

Assess the interests of each stakeholder to determine where conflicts of interest and areas of alignment exist. While assessing these interests is challenging, it is more straightforward than assessing the interests of anonymous token holders, as we can start from on-chain incentive mechanisms. For Blockzaar, for example, the incentive structure aligns the interests of users, client operators, and third-party product and service providers with those of the protocol, involving the distribution of earned commissions. As mentioned above, this is a complex parameter setting determined by the DAO.

At the same time, when it comes to fund management and/or protocol maintenance and upgrades, the interests of these stakeholders may not align. For instance, users may want the DAO's funds to be used for products and services that benefit users rather than those that benefit client operators; third-party product and service providers may oppose such expenditures due to concerns about increased competition.

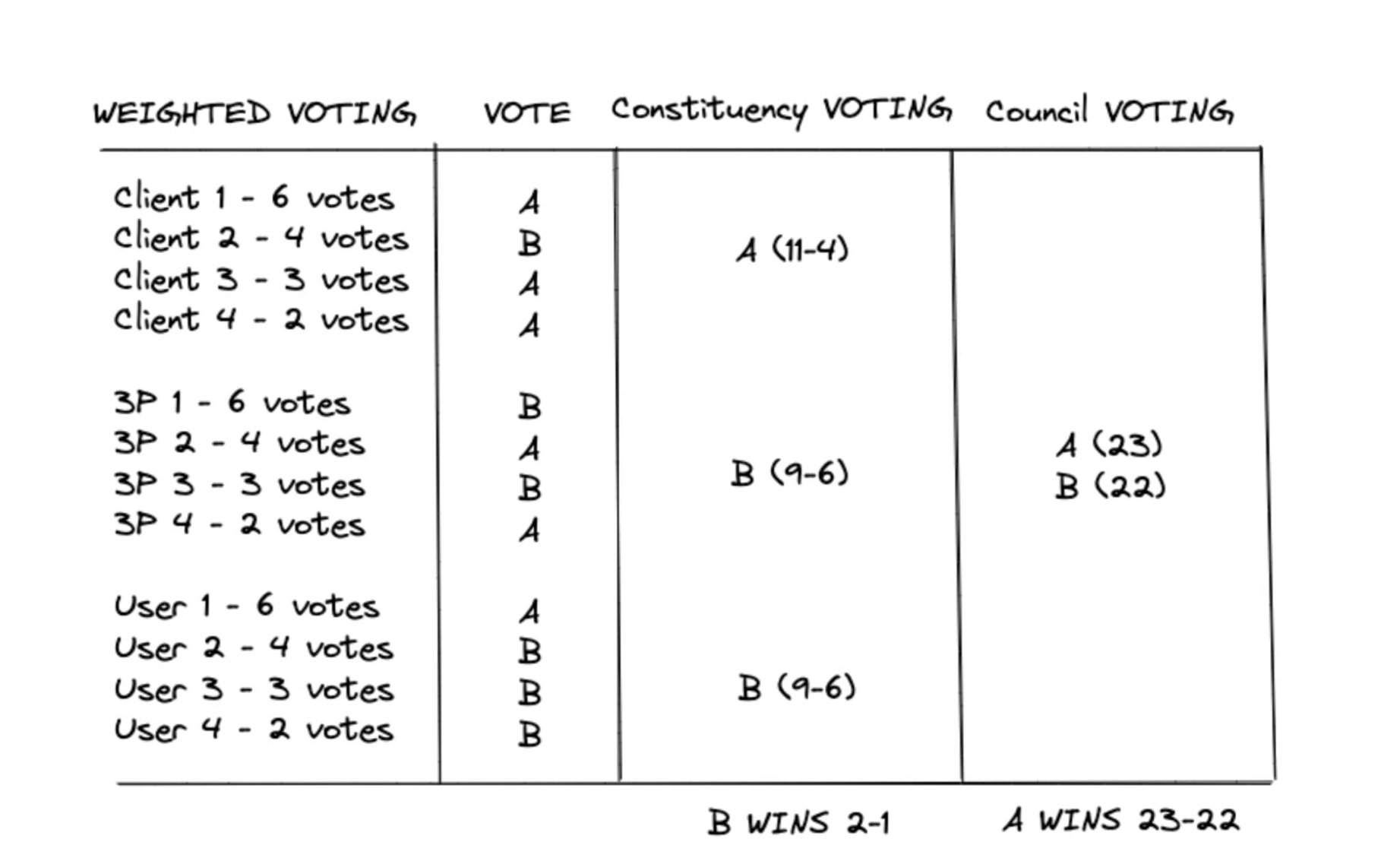

Balance the voting power of stakeholder representatives according to the interests of each stakeholder. This can be achieved through weighted voting, where the best-performing representatives in each constituency receive the most votes, thus promoting competition and opposition among stakeholders. Additionally, single council voting or separate constituency voting can be employed, as illustrated below:

If the same or related parties control multiple clients and/or third-party products and service providers, any stakeholder council will face the risk of "hostile takeover." However, this risk can be partially mitigated by requiring all such parties to have different taxpayer identification numbers in the U.S. or to use some form of personal identification protocol.

Representative Council

The power of the stakeholder council should be checked by the token holders, as token holders inherently have vested interests in the governance of the protocol, which may conflict with the interests of the stakeholders represented by the stakeholder council.

DAOs can control the common issues brought by direct democracy (such as low participation, uninformed voters, etc.) through the implementation of representative democracy, most likely in the form of delegation. Among other things, representatives should be independent of any members of the leadership tier and should receive appropriate compensation for their role in system governance.

The stakeholder council and the representative council jointly have the authority to approve proposals submitted to the DAO. One or both councils can serve as the initial governance layer responsible for creating new proposals, while the other governance layer has negative power (a proposal approved by one council will pass unless vetoed by that council) or positive power (a proposal approved by one council will only pass if approved by that council).

While this setup is similar to the bicameral structure used by Optimism, the key difference is that the stakeholder council of the Blockzaar DAO (like Optimism's Citizen's House) will systematically consist of the stakeholders with the highest production volume in the system. Compared to excellent participants who are not clearly incentivized, these stakeholders are more likely to become vested interests in promoting such systems. Since the livelihoods of stakeholders ultimately depend on the protocol, they are more likely to take the governance of the protocol seriously than those who participate in decentralized governance out of a sense of civic duty. Such an arrangement helps make the DAO function more like an industry consortium rather than a homeowners' association.

This concept of relying on self-interested parties rather than altruistic or noble social designers has also been explored in other fields, including constitutional and international law, where self-interested parties emerged as overwhelming victors.

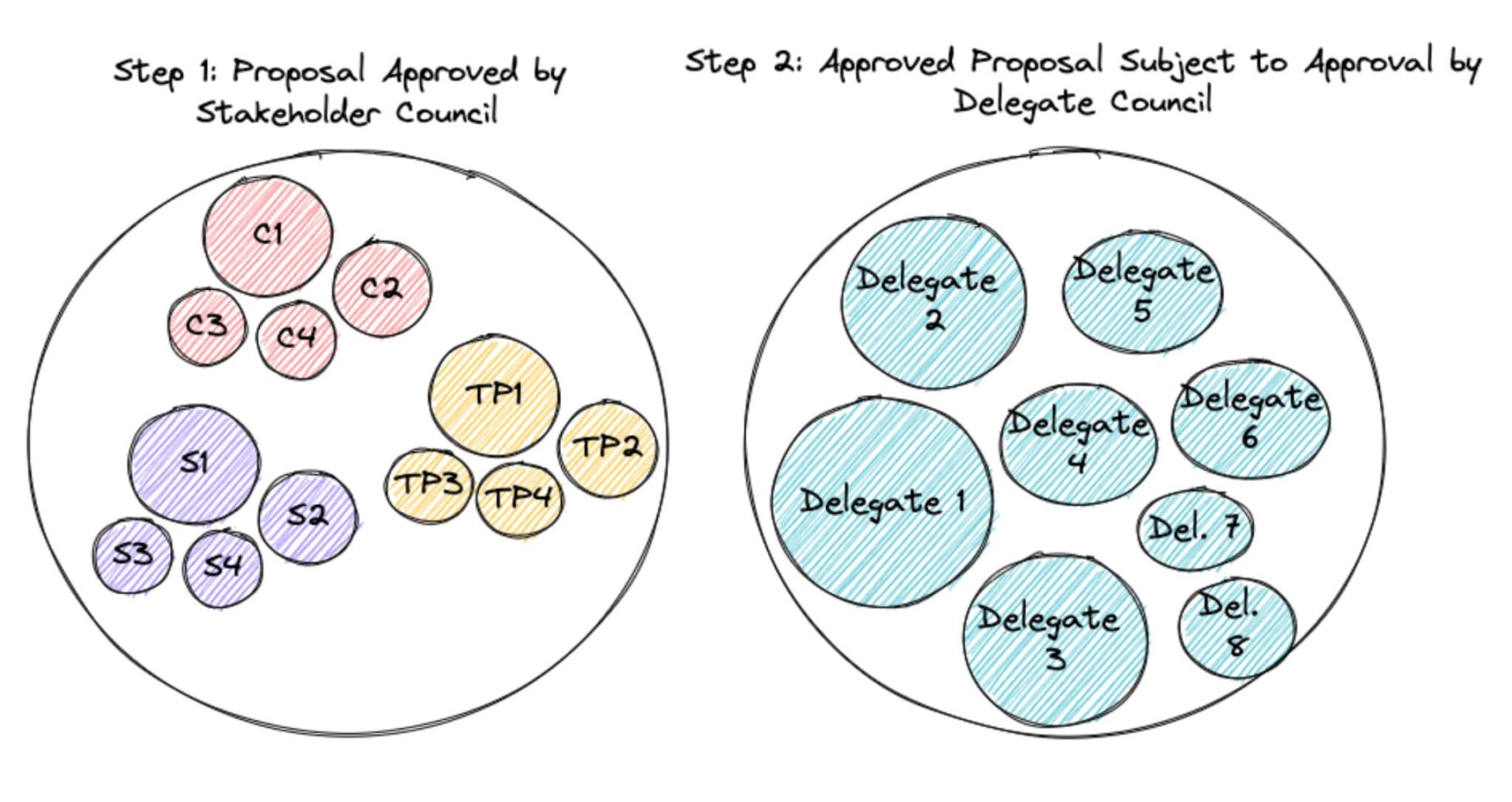

For Blockzaar, the DAO's leadership and governance structure can be set up as follows:

- The stakeholder council consists of: the operators of the top four clients (by transaction volume); the third-party product and service providers that create the top four products and services (by transaction volume of clients using those products and services); and the top four sellers (by transaction volume).

- The voting power of the leadership tier is weighted by constituency and divided into three independent series (as shown above). The leadership tier votes as a single council.

- The representative council consists of 8 representatives elected and approved by token holders, with voting power allocated proportionally based on the number of tokens held.

- Governance changes do not occur by default in the DAO, so any proposal approved by the stakeholder council does not take effect unless approved by the representative council.

An example of Blockzaar's governance system is shown below:

Principle 3: Continuous Change in the Leadership Tier

Machiavellians believe that institutions must not only have continuous opposition but also allow new leaders to forcibly enter the leadership tier to create turbulence and avoid a stagnant balance of power. According to Machiavellians, such changes must be forced, as leadership tiers will always oppose changes to maintain their status and privileges.

Broad community participation has already become a hallmark of the Web3 spirit and often extends to the leadership tiers of DAOs, where community members often become formal contributors to the DAO. However, in token-based voting systems, the ability of community members to gain real power is often limited—because gaining such power encounters financial barriers.

Nevertheless, those DAOs that wish to embrace Machiavellian principles (i.e., the need for the leadership tier to continuously experience turbulence) can introduce turnover in the leadership tier in several different ways, including:

Setting term limits for stakeholders in the stakeholder council. For example, the performance criteria set by the DAO for promoting stakeholders to the stakeholder council can be regularly reassessed, allowing the stakeholder council to re-admit the best-performing stakeholders from the previous period.

Allowing token holders to freely replace representatives, otherwise, representatives' terms will end periodically, at which point new representatives must be appointed.

Empowering token holders to directly elect some stakeholders in the stakeholder council (client operators, third-party product and service providers, and users), thereby establishing that prior performance is not the only pathway to promotion to the stakeholder council.

Principle 4: Reinforcing Accountability in the Leadership Tier

If a large group of people fundamentally cannot hold their leaders accountable (as Machiavellians predict), then DAOs should strive to take measures to strengthen accountability throughout their entire ecosystem.

By implementing the above three principles, Machiavellian DAOs can have stronger accountability than current DAOs, especially because:

- With fewer participants in the leadership tier (compared to the large number of token holders), each member of the leadership tier can better hold other members accountable for their voting history. This is particularly likely to occur between members of the stakeholder council and members of the representative council, given the inherent tension between the two councils.

- If the client ecosystem is too dominant, users can simply stop using certain clients and switch to others, making client operators (including those promoted to leadership) more accountable to user demands. Similarly, a strong third-party product and service provider layer can also hold users and client operators accountable to these providers, as they have the ability to switch to other products and services.

- Regularly replacing representatives and term expirations provide members of the stakeholder tier with an opportunity to lobby token holders, thereby holding representatives accountable for their previous votes.

If client operators, third-party product and service providers, and users are required to "lock" a certain number of governance tokens, then DAOs can also enhance the accountability of their stakeholder councils and representative councils. They can lock these tokens in a smart contract before joining the stakeholder council, which will only release them after a certain period. However, given that members of the stakeholder council may not trust their stakeholder peers and may not want to risk their assets, this mechanism may also be difficult to implement. Therefore, if any locking mechanism is introduced, it may also need to allow stakeholders to "rage quit," similar to the mechanism implemented by Moloch DAO.

If implemented correctly, locking mechanisms will help align the incentives between the stakeholder council and the broader token holders.

Conclusion

A common issue raised by the ruling elite in American corporate governance is that shareholders, directors, and executives of companies often possess unchecked power. As a result, we see CEOs earning far more than employees, or we see boards implementing stock buyback programs instead of reinvesting those resources into the healthy development of the organization, among other issues.

While this centralized power sometimes allows these companies to act more effectively, their mistakes and misjudgments have led to countless failures, with other stakeholders in these organizations having no recourse. Blockchain, smart contracts, and digital assets make the design of Web3 systems unique. DAOs prioritize governance minimization, which will help them maintain credible neutrality, enabling them to develop emerging ecosystems composed of client operators, third-party products, service providers, and users.

Allowing these stakeholders to play a meaningful role in governance gives DAOs a real opportunity to achieve "stakeholder capitalism," which traditional equity/corporate forms seem unable to accomplish. Therefore, we should advocate for Web3 systems to adopt incentive structures that promote actions to improve their systems, making them more productive and better serving all stakeholders, rather than adopting incentive structures that optimize value only for a few owners.

Once again, Web3 should triumph over Web2 through decentralization, as decentralization reduces censorship, promotes freedom, and freedom, in turn, facilitates opposition to power, driving greater progress. By incentivizing competition, empowering opponents, and utilizing non-token voting, DAOs can help accelerate this cycle.

But we must accept and adapt to this system.