Is the Federal Reserve's $300 billion emergency measure enough to stop the crisis?

Written by: Joseph Politano

Compiled by: Block unicorn

After the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, did the Federal Reserve's $300 billion emergency funding to banks suffice?

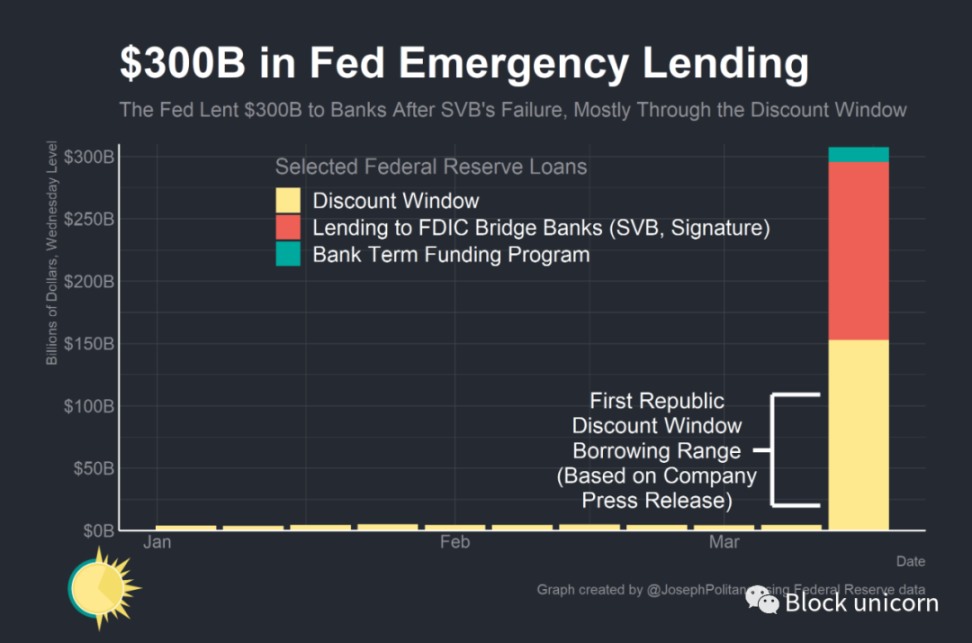

For the first time since 2020, the Federal Reserve has provided emergency support to the U.S. banking system. Following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank last week, several major regional banks are struggling, while the bad assets of these failed institutions are still managed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The Federal Reserve has committed to protecting banks and the financial system throughout the crisis, backing these commitments with strong actions—supporting the FDIC, opening a new bank lending facility over the weekend, easing the conditions for banks' emergency credit lines, and promising liquidity to any distressed savings institutions.

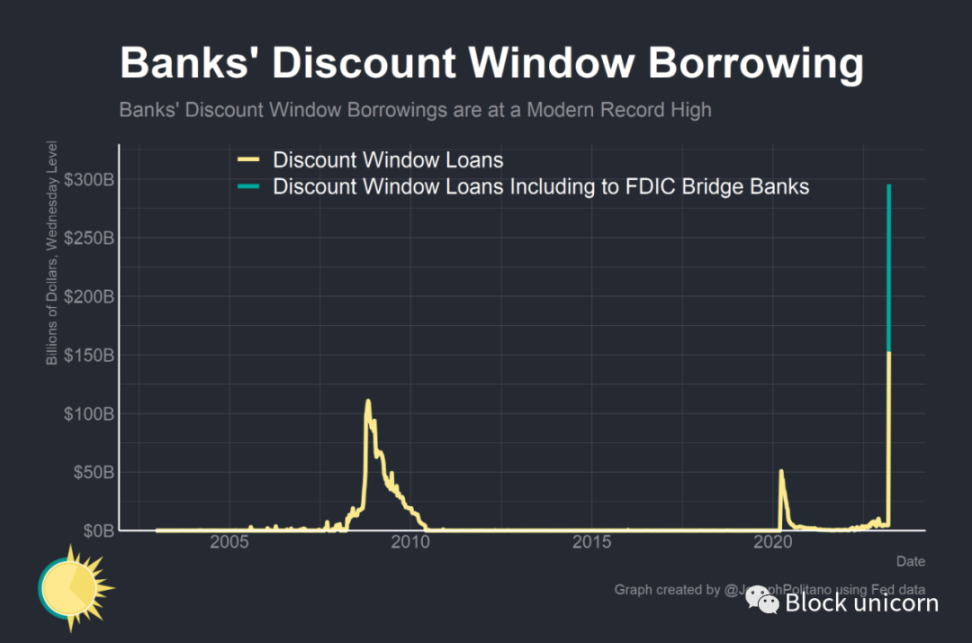

As of Wednesday, they have also provided over $300 billion in new loans to U.S. banks, more than double the direct credit created at the peak of the pandemic in early 2020. So far, this has effectively contained the crisis—since the FDIC, Federal Reserve, and Treasury Department joined forces to respond to the crisis, no more banks have failed in a week—but many banking institutions remain at risk. So, is the Federal Reserve's $300 billion emergency response—and the series of new policies they have implemented—enough to stop the crisis?

Breaking Down the Federal Reserve's Emergency Loans

As of Wednesday, the Federal Reserve has provided over $300 billion in collateralized direct loans to the banking system—more than at any time since the global financial crisis—to mitigate the impact of the collapses of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank. Over $11.9 billion of the loans came from the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), a newly established tool that allows banks to pledge government-backed securities at face value in exchange for loans of up to one year.

However, most of the Federal Reserve's loans ($295 billion) came from the discount window, a tool historically reserved for providing emergency liquidity to banks. The Federal Reserve provided $142 billion in loans to the bridge bank under the FDIC for SVB and Signature Bank, and $152 billion in loans to private banks through the discount window. Of this $150 billion in private borrowing, one private bank may account for most of it—First Republic Bank, which stated that its discount window borrowing has ranged from $20 billion to $109 billion since the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank.

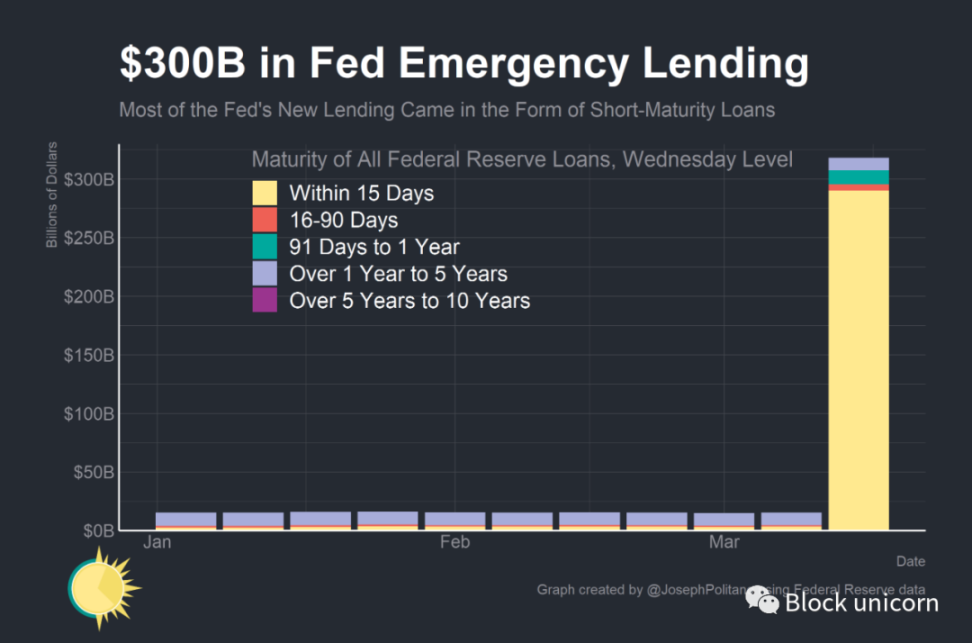

The vast majority of these emergency loans are very short-term, with $290 billion of loans maturing within 15 days, setting a historical record, and only $540 million of loans maturing between 16 and 90 days, almost all of which are discount window loans. Additionally, $11.9 billion of loans mature between 3 months and 1 year, almost entirely corresponding to the loan term of the BTFP.

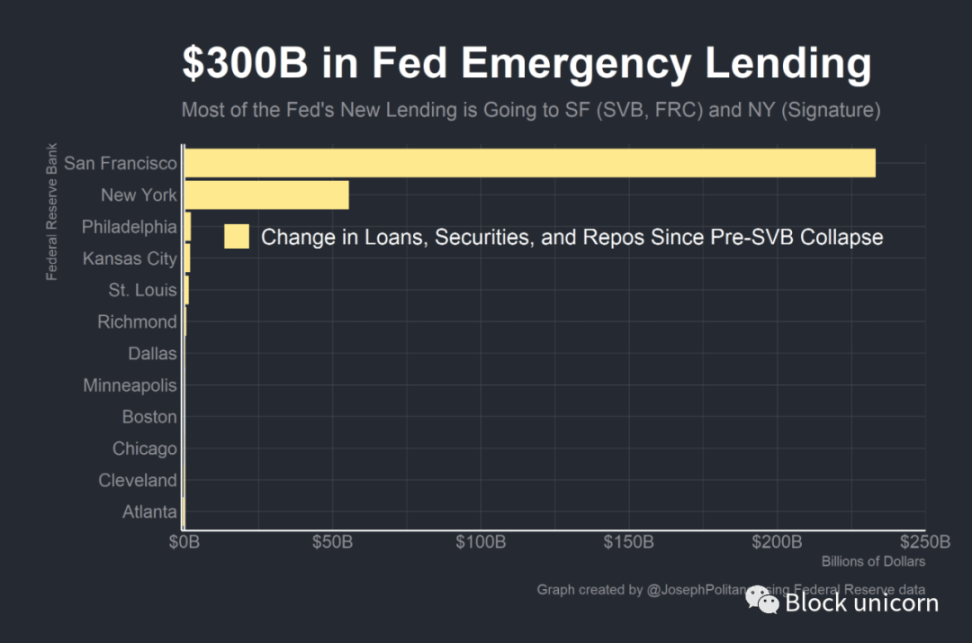

The Federal Reserve intends not to immediately disclose which institutions they loaned to and how much they borrowed, but by examining the total asset data of regional Federal Reserve Banks, we can get a rough idea of who received liquidity from the Federal Reserve. Looking at items including discount window loans and BTFP funding, we can see that the loans are not evenly distributed across the country but are heavily concentrated in two Federal Reserve Banks. The assets of the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank, which has jurisdiction over SVB and First Republic Bank, increased by $233 billion, while the assets of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, which has jurisdiction over Signature, increased by about $55 billion. This does not necessarily mean that all loans are concentrated in the three banks—SVB, Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank—several West Coast regional banks are also in distress, and the New York Federal Reserve Bank has jurisdiction over many financial institutions that are not necessarily only in New York (e.g., most foreign bank organizations)—but it does indicate that the crisis has not necessarily led to banks across the country borrowing from the Federal Reserve.

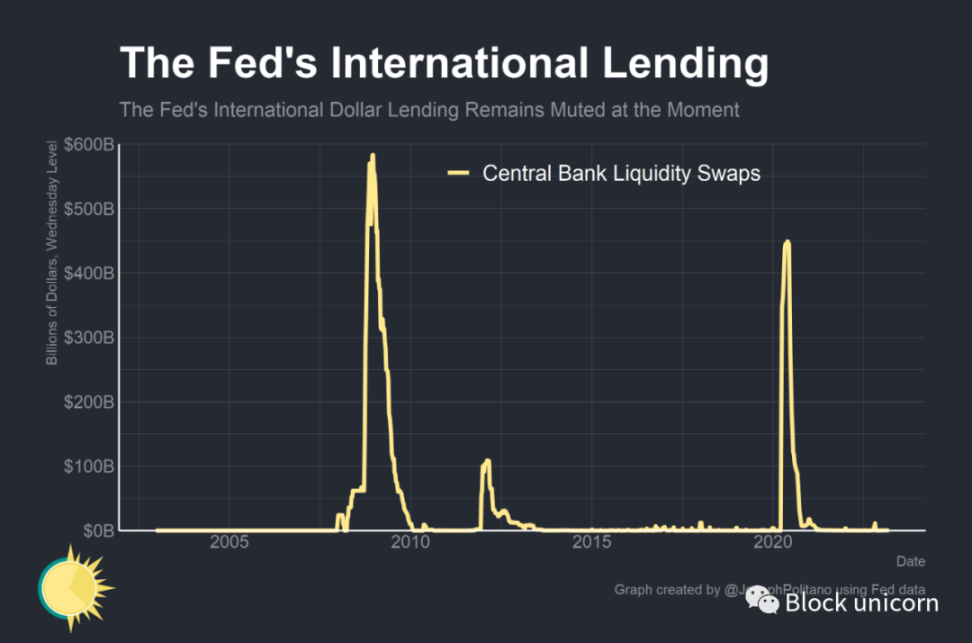

The funds borrowed through the Federal Reserve's dollar swap lines (a tool that foreign central banks can use to provide dollar-denominated loans to foreign banks) are also minimal. Although the recent weakness of foreign financial institutions like Credit Suisse may soon necessitate the use of swap lines, the current suspension of these swap lines means that the crisis has so far been largely contained within the U.S., with the primary recipients of the Federal Reserve's emergency funds being U.S. banks borrowing from the discount window.

Understanding the New Era of the Discount Window

In many ways, the risks posed by the collapse of SVB and its aftermath caught the Federal Reserve off guard. Regulators had taken a lax approach to smaller "regional" banks, mistakenly believing that the failure of these banks would not pose a systemic threat to the financial system, while the Federal Reserve thought that the pace of interest rate hikes had not yet reached a level that would undermine the stability of the banking system. However, to some extent, they were very prescient—the Federal Reserve has been trying to institutionalize reforms to the discount window aimed at improving financial stability after the early COVID financial crisis. Today, the unprecedented use of the discount window reflects, to some extent, the anticipated results of these reforms.

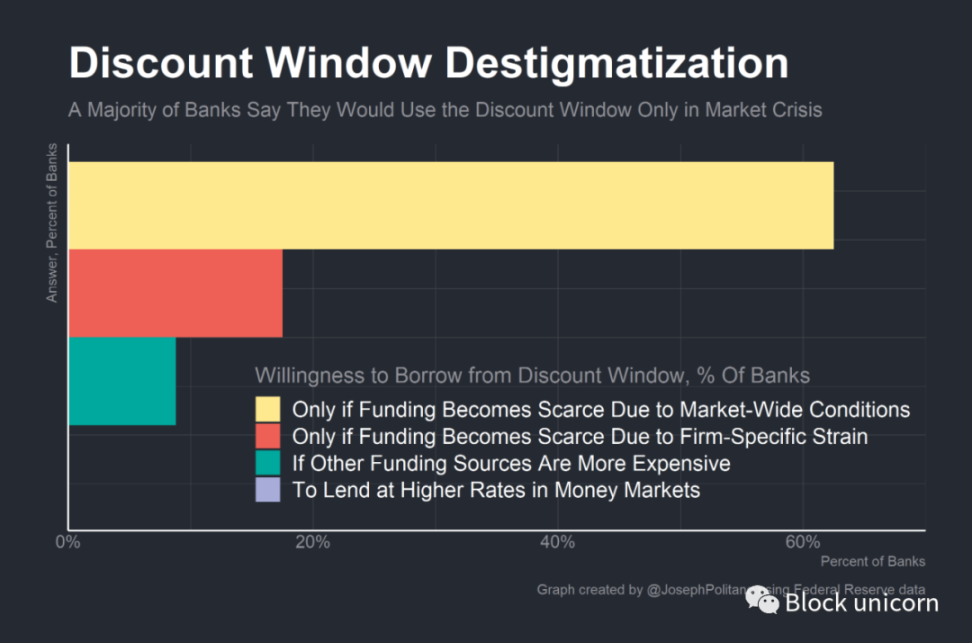

In the early days of the Federal Reserve, many institutions essentially borrowed from the discount window, making it more of a routine monetary policy tool rather than a backstop for emergency support to the financial system. By the late 1920s, the Federal Reserve began to oppose the use of the discount window, believing that excessive reliance on it would breed financial stability risks, and that in an era where the Federal Reserve set policy rates by injecting or removing bank reserves from the system, this tool had become outdated and ineffective. Whenever banks borrowed from the discount window again, the Federal Reserve would tighten requirements, increase surcharges, or further restrict loans to push banks away from the discount window. This led to a serious problem—due to the Federal Reserve's strong opposition to using the discount window, overall usage rates were very low, and any bank attempting to borrow from the discount window in a real emergency would face enormous shame.

Borrowing from the Federal Reserve indicates that banks are in a state of true desperation with no other options. If shareholders, creditors, depositors, or even government regulators find out that you used the discount window, they will not be kind to you—this is essentially a fireable offense for bank executives. The consequence of this is that even innocent institutions under pressure would choose to take on unnecessary financial risks rather than seek help from the Federal Reserve, making the entire financial system more unstable.

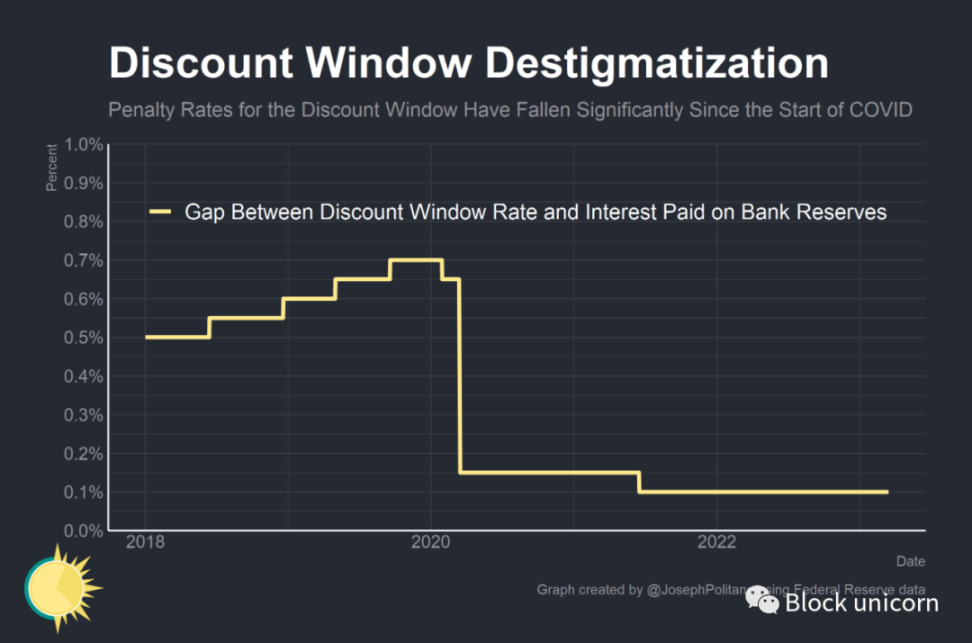

After the financial crisis in early 2020, the Federal Reserve implemented several reforms aimed at encouraging more banks to use the discount window and reducing the stigma associated with borrowing from the Federal Reserve. First, the maximum term was extended from overnight to 90 days, allowing banks to engage in longer-term and more flexible borrowing. Second, the "penalty rate" charged for borrowing from the discount window was significantly reduced, so that the cost of borrowing from the Federal Reserve is no longer significantly higher than market rates—today, the primary credit rate at the discount window is only 0.1% higher than the rate the Federal Reserve pays on bank reserves, compared to 0.7% before the pandemic.

Although using the discount window can damage a bank's reputation, the stigma associated with using the discount window has diminished since the pandemic—over 60% of banks indicated that they would borrow from the Federal Reserve if market conditions led to a scarcity of funds, which was the case before March 2021, and prior to the collapse of SVB, banks frequently borrowed billions from the discount window. The changes to further relax collateral requirements after the collapse of SVB may encourage more banks to use the discount window and help reduce the stigma. The fact that so many banks feel the need to use the discount window is a bad sign for the health of the U.S. financial system, but their choice to use the discount window rather than attempting to cope independently without Federal Reserve assistance is a good sign.

However, ironically, due to its association with the collapse of SVB, the BTFP (Bank Term Funding Program) may ultimately inherit the stigma issues of the discount window. Nevertheless, the $11.9 billion loan balance indicates that banks are not overly concerned about the image issues of borrowing from the Federal Reserve, which is a positive signal for financial stability. If stigma becomes an issue again, the Federal Reserve may attempt to revive or adjust the "Term Auction Facility"—a program from the Great Recession where the Federal Reserve would auction a certain amount of collateralized loans to banks to prevent any financial institution from being affected by stigma for requesting to borrow from the Federal Reserve. However, the Federal Reserve may view the continued use of the discount window as a sign that the system is temporarily functioning as expected.

Conclusion

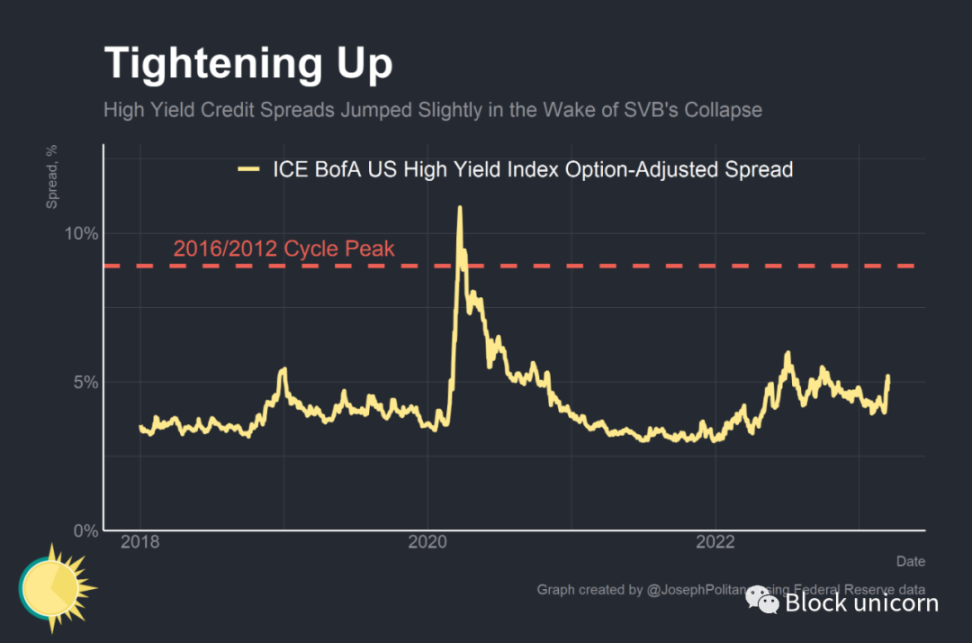

So far, the Federal Reserve's intervention has successfully prevented a catastrophic tightening of financial conditions—although corporate bond spreads have widened significantly since the failure of SVB, indicating that borrowing conditions for major companies have become more difficult, they remain below the recent peaks in July and October. However, this should not be misinterpreted as a sign that the crisis is over— for instance, First Republic has had to absorb $30 billion in deposits from several large banks in addition to borrowing billions from the Federal Reserve. Several banks remain at risk, and the impact of the Federal Reserve's emergency measures on stabilizing the banking system may take time.

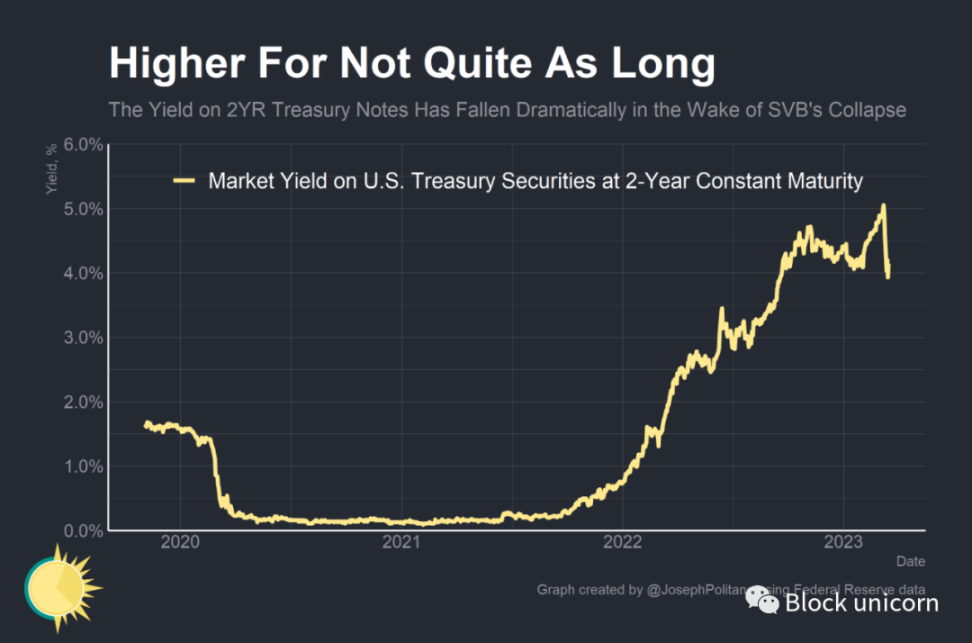

However, one thing is clear—the ongoing effects of the SVB crisis have worsened financial conditions while also lowering expectations for recent interest rates. On March 8, the interest rate futures market expected the Federal Reserve was most likely to raise rates by 0.5% at next week's FOMC meeting—today, they believe it is very likely that there will be no rate hike at all. The yield on the two-year Treasury has fallen by more than 1%, fluctuating wildly over the past week. Due to the deterioration of economic forecasts, banks have been tightening lending—the events of the past two weeks are unlikely to make them more optimistic about future economic prospects. Whether the Federal Reserve's emergency efforts are sufficient to restore confidence in the financial system will depend on whether banks can stabilize without causing a credit tightening severe enough to drag down the U.S. economy.