a16z: Practical Applications of Cryptocurrency Regulatory Frameworks

Written by: Miles Jennings and Brian Quintenz

Compiled by: DeFi Dao

This article is the fourth part of the series "Regulating Web3 Applications, Not Protocols," which establishes a regulatory framework for Web3 to maintain the benefits of Web3 technology, protect the future of the internet, and reduce the risks of illegal activities and consumer harm. The core principle of this framework is that businesses should be the focus of regulation, not decentralized autonomous software.

The framework provides a method for assessing and applying regulation to Web3 businesses, including regulations related to market structure, KYC, privacy, or any other type currently applicable to Web2 businesses. The framework stipulates that regulation should have a legitimate goal, be appropriate to the entities and activities it regulates, and the risks it aims to address, while maintaining true "technological neutrality" (not picking winners in nascent technologies).

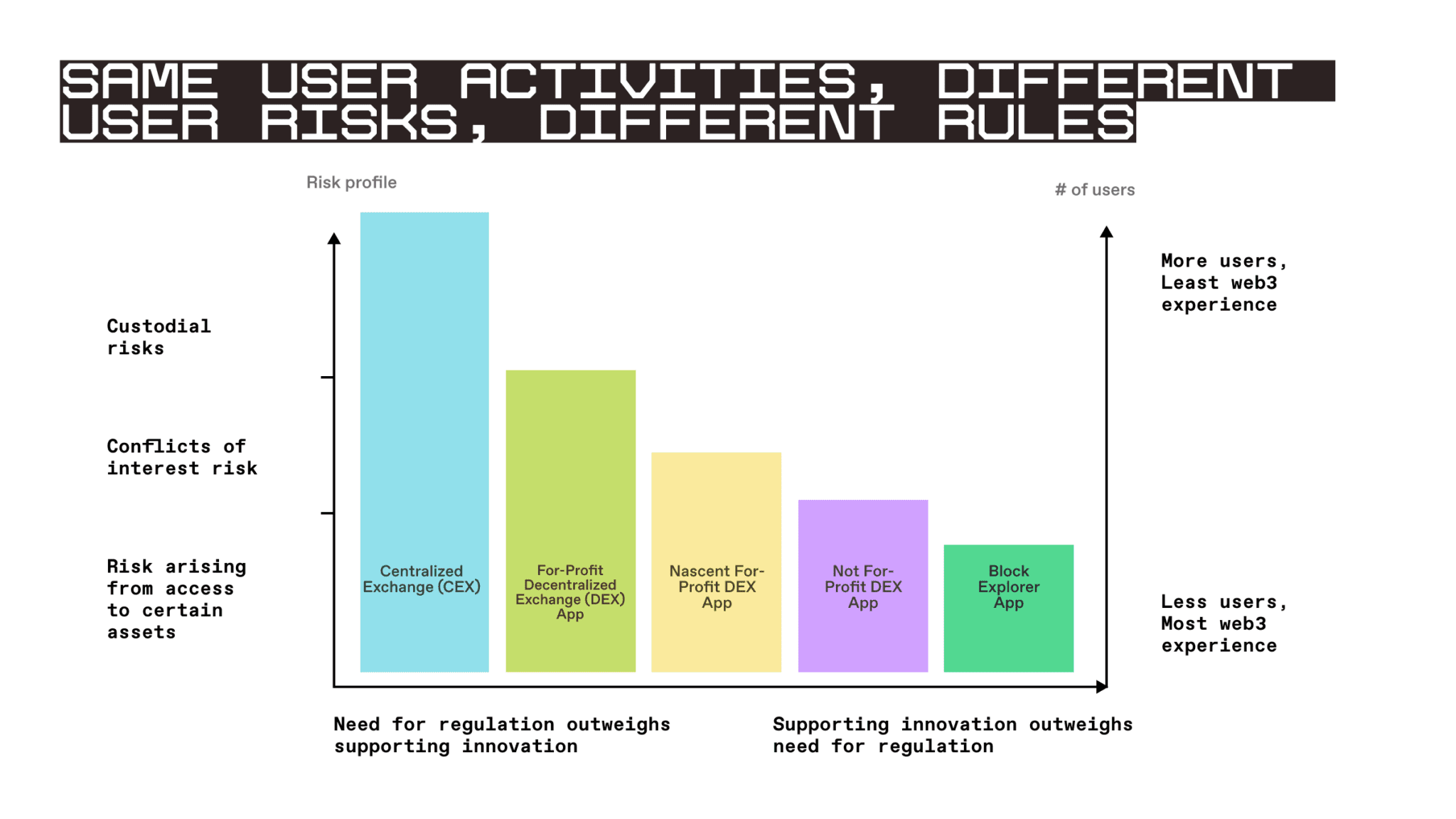

In the fourth part of this series, we demonstrate how this framework can be applied in practice to hypothetical market structure regulation (i.e., legislation and corresponding regulation governing the trading of digital assets on exchanges). We first define the scope of the hypothetical regulation, then explain how different rules and requirements of regulation apply to different types of participants and applications in the web3 space. This analysis shows why the most stringent regulatory requirements should apply to applications that pose the greatest risk to users, while those that pose the least risk should be subject to less regulation. This risk-weighted approach ensures consumer protection while also safeguarding innovation.

While the regulatory examples discussed here focus on crypto-oriented financial use cases, this analysis should indicate that the framework of "regulating Web3 applications, not protocols" can be appropriately tailored for a range of Web3 regulations in the future, including those related to social media, the gig economy, and content creation applications.

Defining the Regulation

In our analysis, we first define the hypothetical regulation to which we will apply this framework and assess whether it should be included under the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA).

Market Structure Regulation

Market structure legislation has been a focus for many policymakers and regulators in 2022 (such as ++DCCPA++, ++DCEA++, ++RFIA++, etc.), who believe that regulation of the digital asset market is necessary. We anticipate renewed efforts in 2023 to push for market structure legislation and regulatory implementation driven by the following policy goals:

- Protect users from risks, including risks arising from custodial relationships, conflicts of interest, and illegal asset trading on unregistered trading platforms.

- Limit the trading of illegal assets, including tokenized securities and derivatives;

- Promote innovation

While decentralized exchanges may be excluded from any market structure legislation and regulatory implementation in the short term, it is unlikely that they will operate forever outside the regulatory scope. Such an arrangement would (1) significantly disadvantage centralized exchanges, (2) potentially reintroduce traditional centralized risks into the decentralized finance (DeFi) ecosystem, and (3) thus undermine the effectiveness of any market structure legislation and regulatory implementation. If policymakers include DeFi within the scope of these legislative and subsequent regulatory efforts, they must appropriately adjust their goals and specific regulatory requirements based on the risks posed by different DeFi entities and activities to the ecosystem and its users.

We assume that new market structure laws will include a baseline requirement that any trading facility that directly facilitates digital asset trading must comply with one or more new implementation regulation registration requirements. The purpose is to ensure that the law covers any exchange (centralized or decentralized) where users can directly trade digital assets. The law also includes certain compliance obligations related to (1) the custody of customer assets, (2) listing rules for digital assets exchanged using the trading facility, (3) record-keeping requirements for all trading activities, (4) trade processing guidelines, (5) conflicts of interest, (6) governance standards, such as establishing system safeguards for operational and security risks, (7) reporting requirements, (8) minimum financial resource thresholds, (9) risk disclosures related to the use of the exchange, and (10) code audits. For our purposes, we will refer to this hypothetical regulation as "the Regulation."

Now that we have outlined the principal requirements of the Regulation, it is worth discussing what the Regulation does not include. First, any market structure legislation could potentially include a statutory definition clarifying when digital assets should be considered securities or commodities, thereby granting the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission or the Commodity Futures Trading Commission specific (or joint) authority to promulgate and enforce the Regulation. However, whether digital assets are securities or commodities is irrelevant to the purpose of this framework, which is an assessment and application of business-based regulation -- rather than asset-based regulation. Digital assets are not an application, protocol, or decentralized autonomous organization (DAO); they are an asset. Therefore, even though many builders and policymakers in web3 are eager for the clarity that such definitions provide, a clear definition is not actually necessary to apply the "regulating web3 applications, not protocols" framework.

Second, any market structure legislation and implementation of the Regulation could also include rules related to other market participants (introducing brokers, brokers, custodians, etc.) and other activities typically associated with exchanges. Regulations designed for these other types of market participants may actually be more suitable for certain decentralized exchange applications, as the nature of the activities of these applications is more similar to those of these other participants compared to traditional exchanges. For example, the functions of a decentralized exchange that guides and directs orders may resemble those of an introducing broker under the Commodity Exchange Act, rather than a typical centralized exchange; or it may be more appropriate to regulatory frameworks like the SEC's "best execution" rule rather than exchange systems. However, for simplicity, we exclude rules applicable to these market participants and treat all applications that directly facilitate digital asset trading and exchange as exchanges. In any case, even if the proposed regulation were to establish rules related to these other participants, the analysis below could be applied in the same manner to assess the applicability of those rules to decentralized exchanges.

Bank Secrecy Act

The Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) -- legislation aimed at preventing criminals from using financial institutions to hide or launder money -- imposes certain obligations on financial intermediaries, including customer due diligence (CDD) and customer identification program (CIP) requirements (applicable to banks and brokers/dealers, etc.), or requires verification of customers and compliance with certain reporting obligations related to customer data and identity verification, commonly referred to as "++KYC++" measures (e.g., applicable to money services businesses or "++MSB++"). Given the role of exchanges in the broader Web3 ecosystem, market structure legislation and implementation of the Regulation could potentially subject digital asset exchange activities to BSA requirements. These requirements have little impact on centralized exchanges, as they are already regulated under the BSA as MSBs; however, applying BSA requirements to applications providing access to decentralized exchange protocols (and not regulated as banks or MSBs) may be unnecessary or unbeneficial. In practice, these requirements could significantly distort the outcomes of the Regulation and ultimately undermine the policy goals behind the Regulation. Here are the reasons:

First, the policy goals of the BSA can be achieved without applying KYC requirements to applications providing access to decentralized exchanges. While BSA requirements assist law enforcement in investigating illegal activities, investigators have been able to effectively obtain the necessary attribution evidence from fiat on- and off-ramps already covered by the BSA, such as centralized exchanges and payment processors (MSBs), as well as banks. For example, existing regulatory measures have applied to money transmitters, including centralized exchanges (like Coinbase and Gemini) and other virtual asset service providers (like Transak and Moonpay), requiring them to verify the identities of users bringing funds onto the chain. This information allows investigators from the private sector, law enforcement, and regulatory agencies to collect attribution information for users conducting transactions through these mechanisms, including any transactions executed via decentralized exchanges.

Second, introducing new significant friction to the user experience of applications providing access to decentralized exchanges could undermine all three policy goals of the Regulation, pushing users from regulated and compliant applications to non-compliant or completely unregulated applications. As discussed in the third part of this series, the emergence of such unregulated or non-compliant applications is an inevitable result of establishing open and permissionless internet protocols. Therefore, effective regulation must be designed to incentivize users to use regulated applications. Requiring all applications to implement KYC measures could have the opposite effect.

The transparency of blockchain provides a powerful incentive for users to protect their privacy -- the unintended (vulnerabilities or hacks) or purposeful disclosure of personally identifiable information (PII) could have devastating effects, exposing users' entire transaction histories and making them potential targets for criminal activities, including identity theft, robbery, and kidnapping. Therefore, users are incentivized to provide PII to as few parties as possible. The motivation and opportunity to evade KYC requirements jeopardize the success of the Regulation, potentially exposing users to greater risks, increasing the trading of illegal assets, and hindering innovation. Additionally, applying BSA requirements to certain applications could, in some cases, raise the possibility of ++constitutional challenges++.

Third, the issue of hindering innovation becomes more complex due to the costs that BSA obligations would impose on startups. In particular, compliance procedures and data privacy costs could prove insurmountable for businesses operating nascent for-profit or non-profit applications, thereby discouraging entrepreneurs from creating and operating these applications. This would reduce the number of applications available to users and decrease competition, which could introduce centralized risks. For example, profitable applications that are able to comply would benefit from a lack of competition, allowing them to exert more influence over the underlying protocols. Ultimately, this could lead to the ++network effects++ of the protocols effectively accruing to these powerful applications (e.g., as more users seek to use the network, they would be directed to the profitable applications), enabling them to extract greater value from users. This dynamic is in stark contrast to the goals that blockchain technology aims to achieve (a free, open, and decentralized internet). This anti-innovation environment would encourage entrepreneurs to build elsewhere and could lead to reduced transparency in U.S. enforcement.

Fourth, adding BSA requirements to the Regulation could undermine the financial inclusivity advantages of blockchain technology. For instance, decentralized exchanges are a key pillar of the blockchain-based financial system, promising to provide financial services, including loans, savings, and insurance, to a broader population than the current banking system. KYC requirements would shorten this promise, reducing the likelihood that impoverished and vulnerable populations, including refugees, could leverage this technology.

In summary, it makes sense that current U.S. laws exclude most applications and protocols from the BSA. As FinCEN explicitly stated in its 2019 ++guidance++, non-regulatory, self-executing code or software itself does not trigger BSA obligations, as software providers are not money transmitters. FinCEN specified that those providing "delivery, communication, or network access services for money transmitters" do not fall under the definition of money transmitters. [31 CFR § 1010.100 (ff)(5)(ii)]. This is because the providers of tools (communication, hardware, or software) are "engaged in trade and not money transmission."

For the above reasons, we have not included any requirements related to the Bank Secrecy Act in the Regulation or our analysis of its application.

Applying the Regulation

Now we will demonstrate the application of the Regulation (without any BSA-related requirements) in practice, including applications with different characteristics, from centralized exchanges to simple blockchain resource explorers. We summarize our analysis in the table below, which charts the relative risks, user numbers, and regulatory requirements for the various types of applications analyzed.

Additionally, we assess the applicability of the Regulation to decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) and developers of web3 protocols and applications. Appendix A lists our findings.

Centralized Exchanges

The registration requirements and ongoing compliance obligations of the Regulation should apply to any business operating a trading facility that directly facilitates digital asset trading through proprietary software rather than through the use of decentralized exchange protocols. In this case, the business decides which assets customers can trade, acts as a trusted intermediary between customers, and serves as the custodian of customer funds -- all of which are provided for profit. The centralized nature of the exchange introduces the legacy risks that the Regulation (and other existing financial regulations) aims to address. Therefore, we expect every requirement of the Regulation to apply to centralized exchanges. However, given that centralized exchanges operate using proprietary software rather than deploying smart contracts on the blockchain, code audit requirements would provide little benefit -- trades within the exchange would be entirely controlled by the exchange, and the execution of those trades would be subject to other requirements of the Regulation.

Decentralized Exchanges

Based on the reasons discussed in the first part of this series, the Regulation should not and cannot directly apply to any web3 protocol, regardless of whether they directly facilitate digital asset trading. Simply put, protocols cannot comply with such regulations. For example, software cannot make the subjective judgments required to comply with listing rules. Even if it could, there would be no way to comply with the conflicting listing rules that each jurisdiction attempts to implement. Without compromising the fundamental principles of the protocols discussed in Parts One and Two, there is no way to apply the Regulation to protocols. That is to say, protocols must be open-source, decentralized, autonomous, standardized, censorship-resistant, and permissionless.

However, if web3 protocols are exempt from the Regulation, then the definition of what constitutes a "protocol" becomes very important. If the definition is too broad, centralized businesses could simply evade the Regulation by using smart contracts deployed on the blockchain instead of off-chain proprietary software. If it is too restrictive, then no protocol would qualify for exemption.

The statutory definition of "protocol" should derive from the fundamental principles of protocols and be balanced with the policy goals of the Regulation. Then, exempting protocols that adhere to these principles would create a self-reinforcing incentive for other protocols to adopt these principles and contribute to an open, free, and ++credible neutrality++ internet.

In particular, protocols that directly facilitate token trading, such as decentralized exchange protocols (DEX), should possess some or all of the following characteristics to qualify for exemption:

- Open Source: Protocols should be open source, as this ensures that the network effects of the protocol accrue to its users rather than to the owners of the protocol's intellectual property. Making protocols open source also ensures that they can be forked by competitors, helping to prevent a protocol from gaining popularity and then seeking to extract significant profits from its users, a practice that has been repeatedly observed in centralized and proprietary systems in web2.

- Decentralized: Similarly, protocols should not be controlled by any individual or centralized party, as such control would jeopardize the credible neutrality of the protocol. Maintaining credible neutrality is crucial for maximizing the network effects of the protocol, as it serves as a strong incentive for third parties to build on the protocol and develop the protocol's network.

- Autonomous: Protocols should generally operate as autonomously as possible. Introducing human intermediaries into the operation of software protocols would significantly undermine the utility of the protocol and introduce certain risks, as these intermediaries could exploit the protocol for their own benefit. In the case of decentralized exchange protocols, certain limited exceptions should be made to allow for the suspension or halting of trades to mitigate potential risks to users in cases of abuse of the protocol. Additionally, allowing for adjustments to certain parameters of the protocol may be beneficial, such as fees generated from specific liquidity pools. However, any such power should not enable the protocol's administrators to materially change the primary purpose of the protocol or control users' funds.

- Standardized: Protocols should leverage standards or establish standards wherever possible to maximize their potential ++composability++. For example, using token standards like ERC20 and smart contract standards can ensure that protocols are more composable, secure, and widely beneficial across the ecosystem.

- Censorship Resistant: Protocols must not have the ability to censor individuals or transactions. While the power to censor may seem appealing, such power would jeopardize the credible neutrality and utility of the protocol, including being easily abused by bad actors. For example, a DAO with the power to change the protocol to censor users could incentivize individuals to seek control over the DAO to censor their competitors. It is conceivable that if the email protocol SMTP had the ability to censor certain providers, large email service providers like Google might seek to leverage their influence to gain control over SMTP and censor competing email services like Microsoft or Apple. Furthermore, the ability to censor undermines the autonomy of the protocol and could expose the protocol to regulatory schemes from global conflicts that would be impossible to comply with.

- Permissionless: Similarly, protocols must be permissionless to maintain their credible neutrality. Like censorship regimes, permissioned protocols can be exploited by bad actors for malicious purposes, as they may attempt to block their competitors from using the protocol. Additionally, the permissionless nature of protocols is crucial for maximizing their potential network effects, which are directly related to the utility of the protocol. If developers need to obtain permission before building a protocol, they are more likely to build in places where such permission is not required. Thus, the effect of a jurisdiction imposing licensing requirements on a protocol would encourage builders to simply develop in jurisdictions that allow for permissionless building.

Decentralized Exchange Applications

In Part Two, we provided a framework for assessing whether a regulation should apply to applications using a protocol. This framework analyzes the purpose of regulation, assesses the characteristics and risks of the applications to be regulated (including whether they are for-profit and whether their primary purpose is to directly facilitate regulated activities), and examines the constitutional implications of applying that regulation.

When applying this framework to many of the rules and requirements of the Regulation, it seems possible to formulate all rules (except regulatory rules) in such a way that applications facilitating access to DEXs would be able to comply. For example, applications should be able to comply with rules regarding listing, record-keeping, and conflicts of interest. Ultimately, as long as these rules do not require applications to control or dominate the operation of the underlying DEX protocol, they should theoretically be able to comply. However, according to the framework, regulatory rules should not apply to any non-regulatory applications -- the risks that these regulatory rules aim to address only arise when applications accept regulation, so applying such rules to non-regulatory applications is meaningless.

Next, we can consider the policy goals of the Regulation and predict that these goals will vary based on the specific characteristics of the applications to be regulated (e.g., characteristics related to the functionality of the applications, whether they operate for profit, etc.). These characteristics reveal where there may be risks of information asymmetry, centralized risks, or market integrity risks arising from the scale and impact of the trading environment. Additionally, these characteristics indicate where the desire to promote innovation may outweigh regulation, particularly for nascent for-profit applications, non-profit applications, and general blockchain explorers.

To illustrate how regulation applies to non-custodial applications using decentralized protocols, we can categorize them into four types: (i) mature for-profit applications, (ii) nascent for-profit applications, (iii) non-profit applications aimed at directly facilitating digital asset trading, and (iv) non-profit applications not aimed at directly facilitating digital asset trading.

Mature For-Profit Applications

Applying the Regulation to mature businesses operating applications that directly facilitate digital asset trading through DEXs presents the strongest rationale. First, if the Regulation does not apply to these applications, the policy goals of the Regulation could easily be undermined. Without compliance burdens, these applications could offer lower trading fees and attract users from centralized exchanges to evade the Regulation. Second, given that these applications are for-profit, they may introduce certain risks of conflicts of interest (related to the display of trading information, fees, or trading routes), similar to the risks posed by centralized exchanges. Ultimately, regulation should be technologically neutral -- not favoring one technology (decentralized exchanges) over another (preferred exchanges) -- unless they have different risk profiles or there are overwhelming policy goals that necessitate different approaches.

One argument supporting the exemption of mature for-profit applications is that the policy goal of promoting innovation outweighs the goals of protecting users from risks and limiting illegal asset trading. As noted in Part Two of this series, the rationale for promoting innovation is supported in web3, given that decentralized protocols effectively become public infrastructure that anyone can use (similar to SMTP/email). Therefore, reducing the compliance burden on applications leveraging DEX infrastructure helps incentivize further development of such infrastructure. However, these applications are mature (they have a large user base and/or high trading volumes), and exempting them from regulation could increase the overall weight of the aforementioned risks, coupled with significant regulatory arbitrage risks, making it unlikely that the goal of promoting innovation would outweigh the other policy goals of the Regulation.

Given these circumstances, these applications may be subject to the same requirements as centralized exchanges unless they do not engage in specific activities (e.g., if they do not custody user assets). Additionally, they should be subject to requirements tailored to their unique risks. For example, we would expect these applications to be bound by code audit requirements, as they utilize smart contracts deployed on programmable blockchains. These audit requirements could also cover the integration of applications with smart contracts to ensure that application providers do not engage in deceptive practices, such as trading ahead of users or quoting users slightly higher prices and pocketing the difference. While these behaviors may be seen by regulators, the erroneous evidence left by these criminal activities may be insufficient to protect users from such activities. Moreover, such activities may be prohibited by other provisions of the Regulation that are more appropriate to the operation of the protocol. Therefore, code audits may be a more suitable requirement.

Conclusion: Subject to the registration requirements of the Regulation, excluding custody requirements but including code audits.

Nascent For-Profit Applications

For nascent or small for-profit applications, the balance of the aforementioned innovation and competitiveness policy goals may lean more towards promoting innovation. For instance, if an application falls below thresholds related to user numbers, trading volumes, or trading commissions, the amount of risk to users and illegal trading would be significantly reduced. At the same time, applying cumbersome regulatory entry barriers or economies of scale costs to nascent or small for-profit applications could be detrimental to web3 innovation, especially in the early stages of technological development. If applicable, the Regulation could effectively become a moat, stifling competition. Therefore, in these cases, the policy goal of promoting innovation may outweigh the risks that the Regulation aims to address. A "regulatory sandbox" or "safe harbor" exempting these applications from the requirements of the Regulation may be appropriate.

However, even if regulators consider nascent for-profit applications to be exempt, consumer protection regulations, such as disclosure requirements, would still help inform users of the risks of using DEXs. Code audit requirements could also protect users of applications from failures of DEX smart contracts while ensuring that the functionality of the applications aligns with their representations. Therefore, a prudent approach may be to condition the exemption of these applications from registration on their compliance with preliminary risk disclosure and code audit requirements, or to require ongoing compliance when risk conditions or code changes occur. This balance would help protect customers while not imposing excessive burdens on newcomers and stifling competition and innovation.

Conclusion: May be exempt from the registration requirements of the Regulation but must comply with preliminary or ongoing disclosure and code audit requirements.

Non-Profit Applications Specifically Aimed at Directly Facilitating Digital Asset Trading

If web3 applications are not operated by businesses for profit, then the relative weight of the policy goals of the Regulation should favor promoting innovation. Non-profit applications are less likely to encounter many of the risks associated with for-profit applications, particularly in terms of conflicts of interest. Additionally, if no one is profiting, there is little or no incentive for conflicts of interest to arise or for operators to facilitate illegal trading.

However, minimum levels of protection can still be achieved by continuing to apply disclosure and code audit requirements. These applications are either developed with the specific purpose of providing users access to DEXs or are designed to guide users to specific DEXs, so they should be responsible for providing users with preliminary risk disclosures and code audit requirements, or for ongoing compliance when risk conditions or code changes occur. Both of these requirements can be easily met, meaning they are unlikely to hinder innovation while still providing meaningful protection for users.

Conclusion: May be exempt from the registration requirements of the Regulation but must comply with preliminary or ongoing disclosure and code audit requirements.

Non-Profit Applications Not Specifically Aimed at Directly Facilitating Digital Asset Trading

If an application is merely a blockchain resource explorer or another general tool interacting with blockchain and smart contract protocols, it should not be subject to the Regulation and its requirements. Applying the Regulation in this case would be akin to directly regulating the underlying protocols, which would stifle innovation. The boundary between regulating software and businesses needs to be protected, and this is most appropriate here. Even the disclosure and code audit requirements discussed above should not apply to such general applications, many of which are tools capable of interacting with every protocol existing on a specific blockchain. Therefore, code audit and disclosure requirements would be impractical, if not impossible, to comply with.

Conclusion: Excluded from all requirements of the Regulation.

Decentralized Exchange DAOs

If a DAO responsible for maintaining and managing DEX transactions can profit from any trades executed through the DEX, then the DAO would effectively be incentivized to promote and encourage trading through non-registered exchanges by providing the loosest and least regulated trading environment, including in terms of asset listings. This would significantly undermine the policy goals of the Regulation regarding user protection and curbing illegal trading. Therefore, to ensure that the policy goals of the Regulation can be achieved, any DAO of a DEX may need to accept certain additional safeguards (including prohibiting the DAO from collecting fees from trades initiated by non-compliant applications and other transactions). For the Regulation, such safeguards could establish the following restrictions:

Decentralized organizations responsible for developing, operating, managing, or maintaining any DEX should be required to (i) utilize reasonably designed mechanisms to prevent the direct or indirect collection and distribution of fees and/or commissions from trades initiated by applications that facilitate digital asset trading and are not registered under and compliant with this Regulation; (ii) refrain from activities whose primary purpose is to promote or encourage trades executed through applications that directly facilitate digital asset trading and are not registered under and compliant with this Regulation.

These safeguards would ensure that the DAO cannot profit from trades initiated by unregistered applications, thereby incentivizing the DAO to encourage and promote trading through registered applications and eliminating any motivation the DAO might have to encourage and facilitate the use of such unregistered applications to evade the Regulation.

Decentralized Exchange Developers

Individuals or businesses developing or releasing software should not be subject to direct regulation. Such restrictions would impose enormous costs with no benefits. An excessive infringement on individual freedoms to successfully stifle the development and release of open-source software would be challenged and defeated on constitutional grounds. However, before such restrictions are ultimately defeated legally, their introduction and approval would have a lasting and irreparable impact on their role in shaping our collective digital future.

Conclusion

Effective regulation of Web3 is an important task, and the existence of decentralized and autonomous global software complicates this task. However, rather than regulating this software, we must focus on tailoring regulations similar to the Regulation for the businesses operating applications on top of it. As outlined above, this process must begin with establishing clear policy goals and include dynamically weighting these goals based on the characteristics of the applications to be regulated. Furthermore, it does not require eliminating the possibility that Web3 technology could be used for illegal activities, but it does require taking measures aimed at reducing the risks of illegal activities and curbing illegal activities. Additionally, safeguards must be in place to ensure that DAOs are not used as loopholes, but in any case, developers themselves should not be regulated.

Ultimately, appropriate regulation of Web3 technology can unlock its potential and add many new forms of native functionality to the internet. This new layer of the network will serve as public infrastructure, upon which millions of new internet businesses will be built.

Appendix A: Summary of Compliance Requirements for the Regulation

*The applicability of these rules will depend on the relative weight of the policy goals behind the Regulation.