Interpreting BNB Greenfield: The Vast Ocean of Web3 Data Storage

Written by: "The Vast Ocean of Web3 Data Storage ------ In-depth Interpretation of the Greenfield White Paper", sukie.eth

Data is the "oil" of the future world, a valuable asset for any country and individual. Data storage services are like barrels of oil floating on the sea; these barrels must be secure enough to hold users' precious data. However, data leakage incidents are happening frequently, which means our data and privacy are like oil leaking into the sea, continuously sold on the black market and threatened at all times. Once such a leak occurs, it is irreversible.

The story of decentralized storage is widely known, starting with the veteran Storj, and the first to provide an incentive layer for IPFS, Filecoin, which begins to depict the vast ocean of FVM. Arweave offers permanent storage solutions for NFT creators, Ceramic's dynamic storage opens new scenarios for on-chain social and data retrieval, Pinata uses IPFS for on-chain storage of NFTs, and EthStorage provides storage Layer 2 for EVM public chains… Now, what new story does BNB Chain's Greenfield want to tell to fill the gap in decentralized storage?

After reading the Greenfield white paper, I feel that the authors have a very clear understanding of the web3 storage track, as well as their own advantages and disadvantages. First, Greenfield defines itself as a sidechain of BNB Chain, rather than creating a new public chain and issuing a new token.

This approach allows it to directly leverage the vast traffic and blockchain data of BNB Chain, without needing to rely on token incentives to complete the early network launch like Filecoin and Arweave. Secondly, it can serve as an expansion of BNB Chain, bringing the outsourced storage industry back in-house, providing more empowerment for BNB. Let's discuss the use cases of Greenfield:

Personal Cloud Storage

This feature allows for the storage of personal data, such as photos and videos. Compared to web2 services like Alibaba Cloud and AWS, it is more resistant to censorship. Compared to web3 services like File AR, it has a lower barrier to entry. It is important to note why IPFS can better protect user privacy and resist censorship compared to web2 cloud storage services.

When our data is stored on centralized cloud service platforms, the security of our data relies solely on trust in that centralized platform. Our data is stored in a few large centralized server rooms. The previous fire in Tianjin almost caused WeChat users' data to disappear overnight, and the recent outage of Alibaba Cloud also proves that centralized cloud storage, while seemingly powerful, lacks true resilience.

IPFS, on the other hand, divides user data into fragments, with a segment of data being stored across different storage miners. The same data is copied to multiple miners, meaning no single machine can possess the complete data. If one miner loses its data fragment, other miners still have backups. These different endpoints are sufficiently decentralized, maximizing the protection of user data privacy and security.

Thus, decentralized data storage does not imply public data, which is different from traditional blockchain technology.

Hosting and Deploying Websites

This is a feature provided for developers, offering Web3 developers a new option for building decentralized frontends.

For example: Uniswap is a decentralized product, but its frontend is still hosted on centralized servers. Regulatory pressures cannot stop Ethereum, but they can prevent access to its frontend, which is why we need decentralized frontends.

Another example is the recently popular Nostr, which is deployed on Flux's Cloud as a decentralized frontend, becoming a truly decentralized social network.

Of course, for Greenfield, this decentralization is relative; I will explain why below.

New Social Media Model

I believe this is BNB Chain's attempt to create its own socialfi product, although related information has not yet been disclosed.

Roughly guessing, the communication and social aspects of socialfi require three main functions: one is a p2p communication tool that can protect user privacy, the second is to establish rights over personal data (NFTs, domain names, posts, social graphs, etc.), and the third is to build a decentralized marketplace to buy and sell the personal data mentioned in the second point.

Starting with storage for socialfi reflects Binance's far-sighted strategy.

Storing Terabytes of Data from BNB Smart Chain and L2 Rollup Transactions

As we know, a single blockchain ensures decentralization and data authenticity through replay, meaning all nodes repeatedly verify data, which generates a large amount of redundant data.

Thus, the aforementioned video and image frontends and other non-core data do not need to be on-chain but can be placed in a DSN (Decentralized Storage Network). For blockchain operational data, such as transactions, although not much, it can still limit the performance scalability of the blockchain.

There are two solutions: one is to improve hardware quality, such as increasing memory capacity and computation speed, allowing a single node to compute and store more transactions, thereby enhancing the capacity and computation speed of full nodes.

However, once hardware performance requirements increase, it becomes impossible to mine using consumer-grade hardware like GPUs. As the hardware threshold rises, centralization issues will emerge. At this point, mining machine vendors will rejoice; there is no better business than selling shovels.

The increased threshold for mining machines also raises costs for miners. Unlike GPU mining and utilizing personal idle storage resources, if there are insufficient economic incentives, miners will calculate hardware and electricity costs, and if profits and losses are unbalanced, they will stop operating nodes, leading to blockchain downtime. If there is no real income to support miners' incentives, then for user data on the chain, miners stopping mining would be a devastating blow.

From an economic model perspective, this situation creates a reverse flywheel: when market conditions worsen, miners sell off, and the more trapped positions there are, the lower the probability of the project's price recovering.

If incentives are excessive, inflation will also be high. Again, if there is no real protocol income, miners cannot obtain sustainable income, leading to endless dumping, which will produce the same result.

Clearly, a storage public chain with lower hardware requirements will have more nodes and greater decentralization. The lowest threshold is to not require mining machines, directly using centralized cloud server services. I have even heard of cases where individuals set up servers in certain third countries using electronic waste for geographical arbitrage. However, regardless of the approach, lowering the performance threshold for storage is a trend in development.

Greenfield states that it will develop towards extreme decentralization (personal terminal hardware mining) and centralization (purchasing services like AWS) at both ends, currently still in the middle ground.

It acknowledges that it is not sufficiently decentralized, but at least miners, or SPs (storage providers), have the freedom to choose between using AWS or Alibaba Cloud.

In addition to improving the quality of full nodes, the second way to address data redundancy is to use Rollup for off-chain storage and data processing. The key here is the sequencer of the rollup; instead of increasing costs to improve full node performance, it is better to take an indirect approach, which only requires increasing the cost of the sequencer and will not affect the decentralization of the blockchain.

However, the question is how to make people believe that the sequencer of the rollup is decentralized and trustworthy?

This brings us to data availability (DA) and data availability sampling (DAS), which I will discuss in another thread.

In summary, Greenfield employs a set of economic incentives and penalties for validators, solving the data availability issue through random access sampling of data shards.

This means that Greenfield also hopes to provide DA for BNB Chain and other L2s.

There is a very interesting point here.

BNB Chain is EVM compatible, allowing seamless cross-chain interaction with BSC, which also means it can fully integrate with Ethereum.

Currently, Filecoin and Arweave have poor interoperability with smart contracts.

@EthStorage is the best chain built on EVM compatibility, after all, it claims to be a storage L2 for Ethereum. If Greenfield is to provide storage for BNB Chain and Ethereum, then at least in this field, it is not the only one doing so. However, I believe Ethereum itself could also undertake such a task, separating DA.

Next, let's talk about the two most important roles in decentralized storage: SP and validators.

SP (Storage Provider) refers to miners, a role that also exists in Filecoin.

Greenfield's mining model is similar to that of Filecoin, where SPs mine by staking BNB and also utilize Filecoin's upgrade feature, Fil Plus, to verify the authenticity and availability of data through validators. Miners who produce valid data earn money, while those who create redundant data lose money.

Reference: https://docs.filecoin.io/store/filecoin-plus/overview/

Another aspect to look forward to is the lending business related to BNB.

Miners need to stake BNB to mine, but this staking usually starts on an annual basis, and withdrawing the stake incurs severe penalties, which greatly reduces the liquidity of BNB. However, many miners cannot afford to purchase such a large number of tokens for mining, so they can choose to stake their future earnings for mining or stake other tokens for lending, which is also a form of leveraging.

From the perspective of this single economic model of storage, we can see BNB

On the demand side, there are:

SP - staking for mining

Customer - paying for data storage

Investor - BNB as a store of value, which can also be lent to SPs to earn interest

On the supply side, there are:

The issuance of BNB, including investor unlocks, mining incentives from BNB Chain and Greenfield, Binance's salary payments, etc. Specifics need to be looked at in terms of token distribution.

The BNB burned through EIP1559 when migrating to BNB Chain.

Currently, Greenfield does not have EIP1559; if it adds user access and other operations that require burning BNB like FVM, this destruction mechanism will increase FOMO.

These are all part of the vast ocean outlined in Filecoin's blueprint, including FVM, lending, and having Dapps, etc. Filecoin aims to first establish storage before moving to smart contracts, while BNB Chain has smart contracts and applications first, followed by storage. This experiment will also answer the question of whether storage or applications came first, the chicken or the egg.

Next, let's discuss why a storage public chain needs lending. This is why I explained supply and demand earlier.

The biggest fear for a storage public chain is a death spiral. Centralized storage can adjust public prices based on hardware and energy costs, but when extreme market conditions hit, miners can only stop operations. This is a huge blow to user data.

In the relationship between public chains and miners, we cannot allow miners to earn too little, nor can we let them earn too much.

The lending interest rate serves as this adjustment mechanism.

This also involves whether storage payments are based on token value or fiat currency.

If it is based on token value, then when storage costs are too high, users will choose other DSNs or go directly to AWS.

The storage costs for users and mining costs for miners are both priced in fiat currency, which is a psychological pricing mechanism.

However, staking and mining incentives can only be based on token value. The exchange rate of tokens to fiat currency also affects the project's fundamentals.

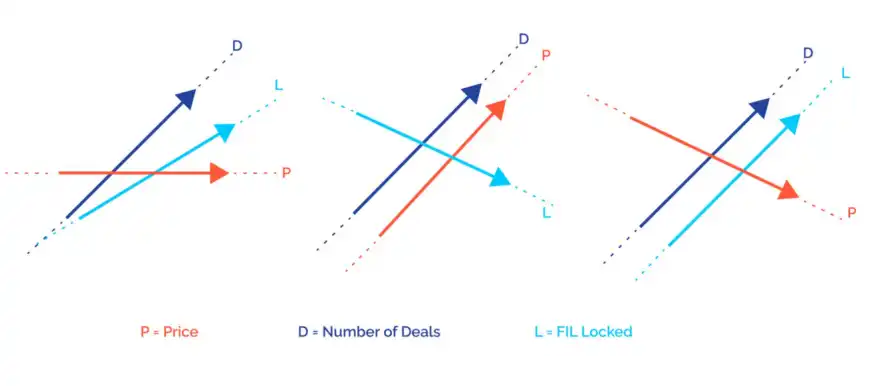

Taking FIL as an example, when the price of FIL drops, SPs need more FIL to store a storage contract equivalent to a dollar value, locking up more tokens and reducing supply.

Miners' demand for FIL increases, and the interest in the lending market for FIL rises, leading to increased demand from investors, thus increasing the demand side.

The price of the token will also rise.

Conversely, when prices rise, miners' demand decreases, interest rates drop, and prices fall.

This achieves price stability and control.

Some have asked me how much impact the launch of Greenfield will have on BNB. Although Greenfield has not yet disclosed its economic model, we can certainly create a mathematical model to hypothesize the impact of BNB's circulation on price under various scenarios.

However, mathematics cannot predict human sentiment, just as I can never calculate whether my dear Chinese billionaire, time management master CZ, plans to pump BNB next. I can only quietly place an order for a few BNB and pray that I won't miss out this time.

(Just joking, in fact, mathematics is really too difficult.)